Viewpoint

Life on earth is a great big challenge. And it’s about to get a whole lot more challenging. The apocalyptic, post-climate-change world-view is a hard one to stomach, but Franny Armstrong has been making hard-hitting films about the Big Subjects since she was in her early 20s, and she’s not going to stop now. Franny lives in a rural part of Devon, overlooking a wooded valley with a gently winding river at its base. Her recently completed house must have had at least some of the villagers in the modest hamlet gnashing their teeth at its standout design. Clad in a blondeish wood, it towers like a big Amish barn, overlooking the woodland and garden that still resembles a builders’ yard. Inside, the living area is cavernous – with a pane of glass along one side of the space. The kids potter about, barefoot and in thin clothing, although it is a chilly, steamy-breath day outside. This is a Passivhaus, explains Franny – designed not to leak any heat out into the environment. It is so well insulated that it requires no heating, other than body heat and the warmth generated by cooking – and solar energy from the south-facing window. A wood-burning stove in the middle of the living space gives out almost no heat to the house, but is used for water heating.

Franny has pretty much always been an activist – the first seeds of environmentalism and social conscience being present in her life from the beginning. With a dad who made documentaries and TV programmes about social issues, a mum who was so passionate about helping her fellow citizens that she’d invite the local homeless man in for a bath, and a Welsh granny who was obsessed with reducing waste, she grew up in a family that set her way in the world. “My grandma would say, ‘don’t rip the wrappers off the presents, we can re-use them.’ She would walk three miles to get tomatoes that were 3p cheaper.

I just thought it was all ridiculous. But then I came to understand that, actually, that’s how you live lightly on the earth.” She and her sister became vegetarians after they went on holiday to a farm and couldn’t bear the thought of animals being killed for food. She was eleven. It was her first consciously activist act. Witness to the inequality showcased in her dad’s films, it is no surprise that she forged the path she has taken.

While Franny Armstrong is not yet a household name in the stable of Ken Loach or George Monbiot, her films have had a profound effect on our consciousness, our corporations, and our media. Her documentary,McLibel, which she began to make at the tender age of 23, followed the extraordinary journey of two

British individuals who stood up to the multibillion multinational McDonald’s. Back in the 90s, such respected media outlets from the BBC to Channel 4 to major broadsheets were regularly in court apologising having been accused of libel by the company. When London Greenpeace published and distributed leaflets criticising the company – from their alleged negative impact on the environment to nutritional value to employee working conditions – McDonald’s tried to make them apologise. One woman – Helen Steel – refused to do so. She was joined by her friend David Morris, and the result made legal and social history.

With borrowed camera equipment from her dad, Franny made a film about the case that impacted the way that we see fast food. Since then, as Franny put it, “There’s been a sea-change in understanding about healthy eating,” with Fast Food Nation and Super-Size Me and a whole phalanx of books and films – right the way through toJamie’s School Dinners. The UK’s legal system was taken

to task at the European Court and found wanting. And McDonald’s has changed its business practice. “The subject got to me on so many levels,” says Franny. “I cared about healthy eating and advertising to kids, and cared about animals, and workers. I cared about censorship and freedom of speech. And I just loved the story of two little people who dared to take on the big corporation.”

That film took three years to make. It was done on a shoestring, against all the odds. “It was Dave Morris, the McLibel defendant,” Franny remembers, “who said the famous words which changed my life, which were: why does not having any money mean you can’t make a film?” After many long years, the court case was not a unanimous win for the London Greenpeace pair, but the story rocked the corporation – and the film got worldwide distribution, was broadcast on TV and cinema round the world and picked as one of the British Film Industry’s ‘10 Documentaries which changed the world’. It was another five years before Dave and Helen finally got their win – at the European Court of Justice, where the English libel laws were found to be failing the defendants. Having moved on to other projects, Franny diligently went back to McLibel and re-cut it with the latest footage. The end result was that British media outlets were no longer afraid of threats of libel action from McDonald’s, and BBC2 finally aired the documentary.

While McLibel touched on the unsustainable nature of our food consumption, Franny’s passion has always been about climate change and sustainability. Her next two documentaries were incendiary, to say the least.Drowned Out showcased the shocking events around the Namada Dam in central India, where villagers were determined to prevent a dam being built – deciding

to stay and drown to bring attention to their cause, rather then accept being moved to city slums. It is one of her trademarks: to bring focus to small groups of people who are daring to stand up to huge, influential corporations, governments and legal systems. While your first thought might be, ‘why do we care about these individuals?’, by the end of the film you realise that it is actually at the grass-roots level that change is often best effected.

This filmmaker is nothing if not committed: when she first arrived at the Namada Dam protests, along with author Arundhati Roy, who was figure-heading

the campaign, she was arrested and thrown in jail. Her sister, Boo, managed to escape with the tapes that they had made, and the story was broadcast on international news, bringing massive attention to the crisis. “I’m a pretty dogged individual,” she nods, sipping tea on the big sheltered deck outside her house. After three years of following the campaign (the government eventually went ahead with its plans, but added compensatory factors such as solar power and rehabilitation of vacant land to benefit the villagers in the region), the film was released in 2002 in cinemas and on TV around the world.

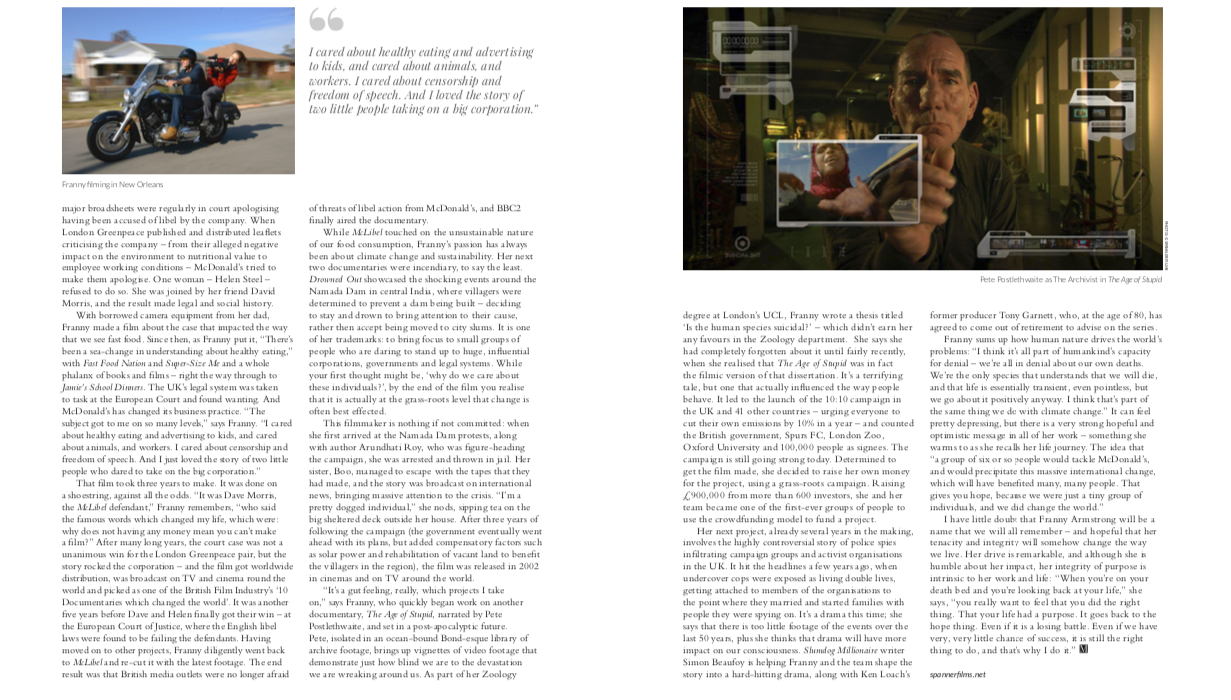

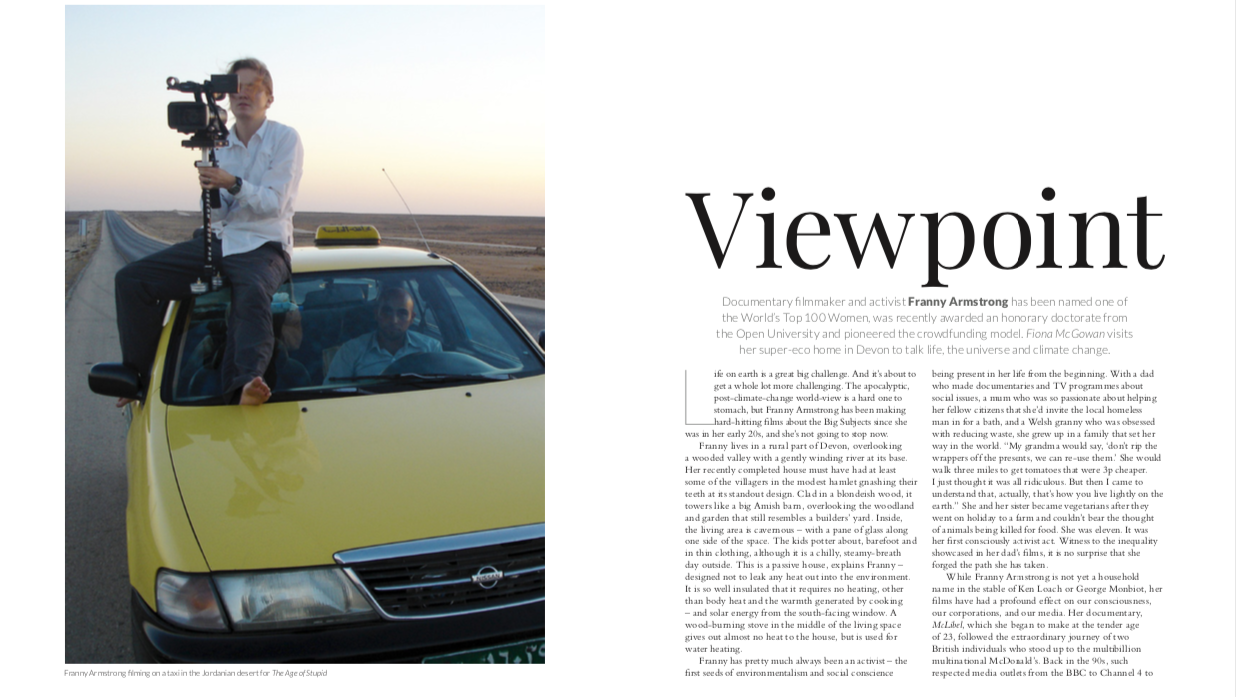

“It’s a gut feeling, really, which projects I take on,” says Franny, who quickly began work on another documentary, The Age of Stupid, narrated by Pete Postlethwaite, and set in a post-apocalyptic future. Pete, isolated in an ocean-bound Bond-esque library of archive footage, brings up vignettes of video footage that demonstrate just how blind we are to the devastation

we are wreaking around us. As part of her Zoology degree at London’s UCL, Franny wrote a thesis titled ‘Is the human species suicidal?’ – which didn’t earn her any favours in the Zoology department. She says she had completely forgotten about it until fairly recently, when she realised that The Age of Stupid was in fact the filmic version of that dissertation. It’s a terrifying tale, but one that actually influenced the way people behave. It led to the launch of the 10:10 campaign in the UK and 41 other countries – urging everyone to cut their own emissions by 10% in a year – and counted the British government, Spurs FC, London Zoo, Oxford University and 100,000 people as signees. The campaign is still going strong today. Determined to get the film made, she decided to raise her own money for the project, using a grass-roots campaign. Raising £900,000 from more than 600 investors, she and her team became one of the first-ever groups of people to use the crowdfunding model to fund a project.

Her next project, already several years in the making, involves the highly controversial story of police spies infiltrating campaign groups and activist organisations in the UK. It hit the headlines a few years ago, when undercover cops were exposed as living double lives, getting attached to members of the organisations to the point where they married and started families with people they were spying on. It’s a drama this time; she says that there is too little footage of the events over the last 50 years, plus she thinks that drama will have more impact on our consciousness. Slumdog Millionaire writer Simon Beaufoy is helping Franny and the team shape the story into a hard-hitting drama, along with Ken Loach’s former producer Tony Garnett, who, at the age of 80, has agreed to come out of retirement to advise on the series. Franny sums up how human nature drives the world’s problems: “I think it’s all part of humankind’s capacity for denial – we’re all in denial about our own deaths. We’re the only species that understands that we will die, and that life is essentially transient, even pointless, but we go about it positively anyway. I think that’s part of the same thing we do with climate change.” It can feel pretty depressing, but there is a very strong hopeful and optimistic message in all of her work – something she warms to as she recalls her life journey. The idea that “a group of six or so people would tackle McDonald’s, and would precipitate this massive international change, which will have benefited many, many people. That gives you hope, because we were just a tiny group of individuals, and we did change the world.”

I have little doubt that Franny Armstrong will be a name that we will all remember – and hopeful that her tenacity and integrity will somehow change the way we live. Her drive is remarkable, and although she is humble about her impact, her integrity of purpose is intrinsic to her work and life: “When you’re on your death bed and you’re looking back at your life,” she says, “you really want to feel that you did the right thing. That your life had a purpose. It goes back to the hope thing. Even if it is a losing battle. Even if we have very, very little chance of success, it is still the right thing to do, and that’s why I do it.”

spannerfilms.net