Field of Dreams

James Risebero’s hero is Le Corbusier. He of the concrete-heavy Brutalist architecture that spawned thousands of copies around the world: not least West London’s iconic beast of a tower block, Trellick Tower. Le Corbusier, of course, was also renowned for his pared-back furniture – all spindly chrome legs and big, masculine leather seat pads: veritable style icons of mid-century modern design.

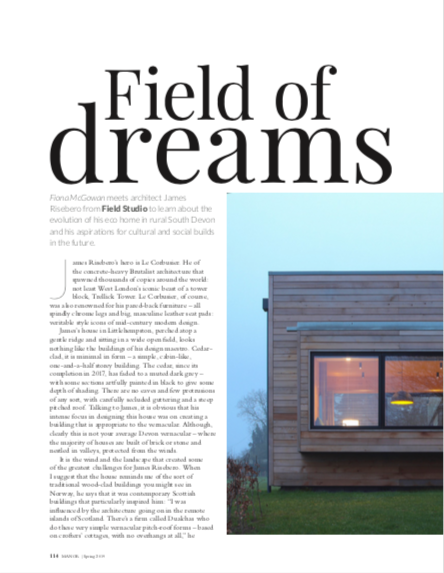

James’s house in Littlehempston, perched atop a gentle ridge and sitting in a wide open field, looks nothing like the buildings of his design maestro. Cedar- clad, it is minimal in form – a simple, cabin-like, one-and-a-half storey building. The cedar, since its completion in 2017, has faded to a muted dark grey – with some sections artfully painted in black to give some depth of shading. There are no eaves and few protrusions of any sort, with carefully secluded guttering and a steep pitched roof. Talking to James, it is obvious that his intense focus in designing this house was on creating a building that is appropriate to the vernacular. Although, clearly this is not your average Devon vernacular – where the majority of houses are built of brick or stone and nestled in valleys, protected from the winds.

It is the wind and the landscape that created some of the greatest challenges for James Risebero. When I suggest that the house reminds me of the sort of traditional wood-clad buildings you might see in Norway, he says that it was contemporary Scottish buildings that particularly inspired him: “I was influenced by the architecture going on in the remote islands of Scotland. There’s a firm called Dualchas who do these very simple vernacular pitch-roof forms – based on crofters’ cottages, with no overhangs at all,” he explains. “Partly, that’s because of the extreme wind. You don’t want eaves, because your roof can literally become detached from the walls.”

It was by no means the first style he fell upon – after finding the plot while on a cycle ride (James is a passionate road-biker), he struggled with various concepts. “The form was always similar, but in terms of the design, I tried lots of different versions. I tried a flat-roof version. But because we’re on the top of a hill, it felt a bit uncomfortable.” It was the pitched-roof concept that eventually won out: “I kept coming back to something similar to what you see here,” he says, looking appreciatively at his comfortable family home. “At some point, I just had to down tools and run with it.” The design process took three years – not least because James was initially trying to do it in his spare time, while working at local Devon practice, Gillespie Yunnie. He eventually realised that he would have to work full-time on his home, and so left the practice. “The design process took about two years, including the detail design. It being my own house, I did about 160 detailed drawings. There was no room for error in the building of it.” Those years of preparation paid off in the build time: “It was a very smooth building process. There were no arguments. No errors, really.”

Like many of today’s architects, the environmental impact of buildings is foremost in James’s mind when designing. Having cut his teeth working at the hi- tech Norman Foster practice – where one of his major projects was the Canary Wharf underground – he more recently worked at award-winning pioneers of environmental architecture, Feilden Clegg Bradley Studios (FCB Studios). That experience, and his personal interest, led him to create an eco-house of his own. There is an array of solar PV panels in a hedged- off corner of the 2.7-acre field, providing 4KW of energy – “and what we don’t use, we export to the national grid,” he says.

There is an air-source heat pump, which extracts heat from the air to warm the water and underfloor heating in the house. It works on the same principles as ground-source heating, explains James. While it is slightly less efficient, due to the vagaries of air temperature as opposed to ground temperature, it is more cost effective than tunnelling underground to set up extensive piping systems. He briefly considered building his house on Passivhaus principles – creating a structure within a strict set of parameters to enable an airtight, self-heating, self- cooling building – but decided against it, mainly because he wanted to incorporate big patio windows overlooking the field and the view across the valley below. Passivhauses generally require a much higher wall-to-window ratio.

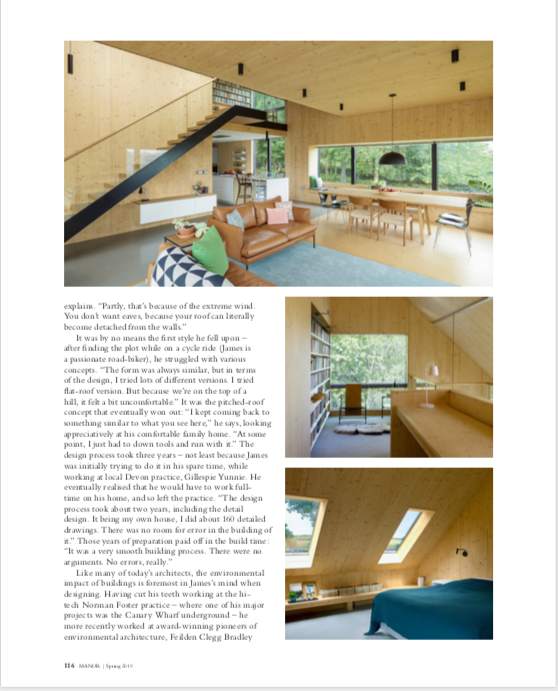

The interior of the house is Tardis-like. While the exterior is a simple, understated L-shape, with steep roof studded with an even line of skylights, the interior feels cavernous – all high ceilings and big, open angles. The kitchen and living space is airy, with light pouring in from giant windows on the south and east sides. A gallery overlooks the room, and the furniture is a careful collection of mid-century modern (James’s yen for Corbusier making an appearance). Most impactful, though, is the prevalence of golden wood – the house actually has a natural scent of it. The walls and ceilings are all made from thick panels of spruce, but this is not just arty cladding. The swathes of wood form the actual structure of the building.

Think of a pre-fab building, where the panels of MDF are carted into place with a crane – and then think again. Field House has no timber frame – its walls are made of sheets of cross-laminated timber. Constructed from offcuts of sustainable spruce, the walls are a thick sandwich of three layers of wood, with the grain going one way on the outer layers and the other way in the inner layer. The roof panels are even thicker, says James, made of five laminations, so they’re 140mm of solid timber. The panels get shipped from Austria and erected in three weeks. A weatherproof scaffolding ‘hat’ is added, so that builders can get to work adding roofing, exterior cladding, insulation and all the other elements of the build.

This form of building structure appeals to James for a number of reasons. It is highly environmentally friendly. Using offcuts of wood is key, as is using sustainable wood. Being so thick, it is a natural insulator, and having no cavities like your usual brick/plasterboard combo, it doesn’t have any ‘cold-bridging’ where heat travels through breaks in the insulation. And using masses of wood, adds James, means that his house is a carbon store: “While this is in existence, that carbon is removed from the atmosphere – it’s stored in the wood.” It is also architecturally pleasing: “I suppose because I’m steeped in the modernist tradition of truth to materials, this seemed like a very honest way of building,” says James. “I love the feel of it and the solidity of it, and the fact that you can use it monolithically.”

Aesthetically, it feels very Scandinavian, especially with the mild sauna-like aroma. The two big living areas downstairs are clutter-free and lend themselves well to the modernist lines of the furniture. The utilities and services have been cunningly placed in the core of the house – so there is no intrusion on the flow of the living space. Upstairs, the gallery houses bookshelves that form the family’s library. There’s a long workbench used as a homework space, and table football. “It’s gone from a library to something like a hot-desking space in an advertising agency,” grins James, wryly. James’s wife, Kate, has a large office space from where she runs her community-based education CIC. It has been cleverly designed as a standalone space with separate entrance and shower room: “We’re trying to think about how we might use it in the future. We could rent this little portion out.”

The four bedrooms are in the steep eaves of the house, but such is the angle of the roof that there is no need to bend down in any of the rooms. The ceilings are high and the views from the long, low Veluxes are superb. James designed the proportions of the rooms around Ikea carcass sizes and added grey touch-release Ikea kitchen units as storage space.

Now that Field House is a fait accompli, James has more time to dedicate to his solo practice. He has taken on a few residential projects – one of which is

a new build with similar aesthetic form to his own. But he wants to take advantage of the freedom of having his own practice to focus more on his passions.

Architecturally, he is particularly keen to work more on the social aspect of building design. Having worked on public buildings with FCB Studios (he designed the RAF Museum in Hendon and the Cold War Museum in Wolverhampton), he realised that: “The things that really interest me are cultural projects. They tend to be very interesting buildings with an interesting set of requirements, often on interesting sites as well.” He is also keen on developing Field Studios to focus on “housing rather than houses”. James feels strongly that “architecture is a social profession. Architecture at its best fulfils a social need.” The idea that he might be able to take on projects for low cost or social housing definitely appeals: “I think there is satisfaction to be had for working within tight budgetary constraints. Coming up with something innovative, with limited means. That’s always something that’s interested me.”

Working from his purpose-built studio next to his home is ideal. He gets to spend time with Kate and the two children, and he can also indulge in his enthusiasm for working outdoors – planting trees and hedges and managing the land (“I used to have a summer job as a landscape gardener”) – as well as cycling and making music in his dedicated music studio. This seems to be a family that has got its work-life balance completely (if not annoyingly) sussed.

fieldstudio.co.uk