The Poetics of Space

Squatting on the south bank of the Thames, Battersea Power Station looms against the skyline like an upturned table. To say it is iconic is as superfluous as saying that St Paul’s Cathedral is a well-known London landmark.

This gigantic testament to London’s energy-guzzling growth took nearly 20 years to build. Its exterior was designed by Giles Gilbert Scott: the same architect who created the (iconic) red telephone boxes and the (iconic) Bankside power station – now home to the Tate Modern. Architect Theo Halliday added lavish Art Deco features to the biggest brick building in the world, earning it the nickname ‘The Temple of Power’. Fast forward to 1977, and a fairly well-known rock band called Pink Floyd stuck a picture of it on their album cover, immortalising the giant powerhouse beyond the reaches of the Thames, and into the consciousness of millions of young minds.

As a child, I remember travelling to London by train and seeing great plumes of smoke pouring out of two of the four cylindrical ‘legs’ of the table – only half of the coal-fired power station was operational at that time. By 1983, all of the chimneys had given up smoking, and Battersea Power Station was closed down. A constant refrain since then has been: what will be done with this extraordinary building? Plans and dreams came pouring in, and the place changed ownership from one huge investor to another. Would it become an indoor theme park (I remember that one well)? Or a retail and leisure facility? Would it incorporate an eco-dome or could it become a biomass power station? None of them came to being, and over 30 long years it seemed as cursed as Tutankhamun’s tomb, as one developer after another gave up and passed it on.

In 2012, a Malaysian consortium of investors stepped in and finally turned the tables on the site, offering £8bn to create a luxury accommodation and leisure development. With that sort of investment, bringing in some of the world’s best architects was a given – Frank Gehry and Norman Foster for the buildings; Bjarke Ingels for the outdoor spaces. Throwing their hat into the ring for the interior architecture was Michaelis Boyd – a company renowned for smaller, super high-end projects including the renovation of Babington House near Bath; the award-winning Sandibe Safari Lodge in Botswana; Soho House and The Electric Cinema; David Cameron’s renovated home; and co-founder Alex Michaelis’s semi-sunken Notting Hill house. Having never worked on a development of these proportions, and rarely employed to work exclusively on interiors, Alex Michaelis says they were thrown in as a wild card: “We were up against all the usual development suspects... We didn’t really think we had a chance.”

Michaelis is a quietly spoken maverick. The son of a famous architect, he was initially determined to eschew the profession, aiming to become a doctor, but soon gave in to his passion for design and architecture. Fifteen years ago, he joined forces with friend Tom Boyd to create Michaelis Boyd. While many of Alex’s projects seem ultra-modern in form, he also rejects many of the expectations of slick, modern architecture. The firm’s pitch for the Battersea job is just one example: “We decided to really do something that was true to what we do, and not something that would seem too developer-y,” he explains, leaning his rangy frame back into the chair. “Something that was more tactile. I always do things that are connected to the place, so our plans were related – in both materials and time – to Battersea Power Station.” Demonstrating his point, Alex pulls up images of some of the apartments that Michaelis Boyd has designed. They have that New York-loft apartment combination of exposed brick and smooth expanses of plastered wall. Huge windows and high ceilings. Ultra-slick open-plan kitchen layouts are startlingly lifelike, and yet the apartments haven’t been built yet. They are all actually CGI – created by Michaelis Boyd’s ‘Real Life’ in-house CGI department.

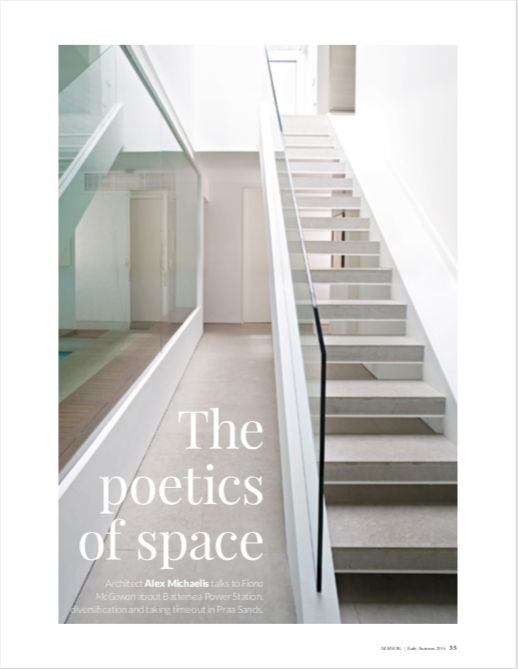

Another case in point for Michaelis’s rejection of the clichés of whitewashed modernism is his holiday home in Praa Sands – just along the coast from Porthleven, and 15 minutes’ drive from Penzance. Built on the site of a dilapidated cottage, the quirkily misnamed ‘Little Cottage’ is now a Deco-esque marvel – all curved white walls and a giant 30ft window, set in a gem-like green lawn which drops impressively away to a low cliff and a stretch of beach below. Sitting in the open-plan kitchen-cum-living room, it is impossible not to be transfixed by the huge vista. It is reminiscent of a Malibu beach home, or, as Alex says, some of his favourite beachscapes in Mozambique and Kenya. “I think that’s why I bought it,” he says, “because it felt like Africa. You get this big, wide view. On a hot day, it just feels bigger.” Little Cottage is in a stunning location, and the architecture and interior design is, needless to say, as good as it gets. However, it is very much a home. The box-like bedrooms upstairs have the expected smooth lines and minimalist décor – there are no paintings or cosy touches – and the eye is simply drawn to the large, square, floor-to-ceiling windows that are filled with that ever-changing view of the sea. The walls are unpainted render, a design feature chosen by Alex. “I’ve always loved unpainted plaster and the way it has depth and ages. I actually like the repair patches, too.”

Alex and his wife Susana – who have seven children between them – clearly love this place. Life in London is frenetic: an endless cycle of school runs and parties, work and jet-setting. It is to Praa Sands that the family come to relax and settle into a different rhythm of life. Six times a year, they descend on the place – which is partly why Little Cottage feels so homely. The rest of the time, it is rented out through luxury boutique accommodation brand Beachspoke – sleeping eight, it’s not cheap: prices reach £5,000 a week in peak season. Visitors to the property soon discover what charmed Alex and Susana – the accessibility of the beach, the wide stretch of garden and giant open-plan living space with its massive table, which seats at least a dozen guests. It is ideal for one large family, or two smaller families. Alex ticks off some of the family’s favourite activities when they are down: surfing is a hot favourite – Susana tells of how she was boogie-boarding with a pod of dolphins, and Alex had a close encounter with a seal recently, “It was quite scary, actually.” The trampoline in the garden is well-used, and the blonde-wood floor is comfortably scuffed. Like the smooth imperfections of sun-bleached driftwood, the whole property perfectly combines its modernist lines with a holiday, beachy feel.

Over the years, Alex and Susana have loved discovering the best things about the area. They enthuse about fabulous restaurants in nearby foodie haven Porthleven: “We really like [Asian-fusion eatery] Kota Kai and Rick Stein,” says Alex, “and there’s a fantastic crab shop there, run by old ladies who don’t like crab. And the fisherman who no-one knows about with the crappy cardboard sign – last time we bought a huge piece of monkfish from him that fed everyone. The kids like jumping off the harbour wall in Porthleven, too.” Catering is always going to be a challenge, but with a big Weber pizza oven and barbecue grill outside, the spacious open-plan kitchen, and some very large pots, they make it work. “Sometimes we go and pick mussels off the rocks down there,” says Susana, pointing out towards the rocky eastern edge of Praa Sands beach, “and make moules mariniere for dinner.”

Alex is constantly creating – even on a few-day visit to Little Cottage. They are currently converting a garage into a studio place (great for the teenagers: with all that open-plan living, it’s hard for the younger children to get to sleep when the teens want to stay up late). They have only recently completed their new London home near Shepherd’s Bush: a narrow, turret-like building tucked into a small space between buildings, but stretching way back to incorporate a second oval shaped building, indoor swimming pool, fireman’s pole, courtyards, a roof garden and a bridge connecting the two buildings.

Leaning forward on the long table that’s covered with coffee cups, magazines, newspapers and cuttings, Alex talks about his business. The property market, he believes, is crazy – and likely unsustainable. The 254 flats in Battersea Power Station have a starting price of a million pounds, and rocket up to £5 or £6 million for a penthouse. In the face of this craziness, Alex and his partners believe in diversification. “My view on design is that architecture and interiors and graphic design are not separate entities any more. Everything’s related. You need to embrace it all and break down the boxes that we’ve made for different professions or parts of the design.” This is why Michaelis Boyd has businesses devoted to CGI, brand and website design, as well as furniture design and sculpture – creating a range of items, from a chess set and board games to a table and chairs. His wife is an art curator also advises on interior design. “I’m more involved in the interiors, the finishing and the usability,” she says, looking meaningfully at Alex. “I’m constantly trying to encourage more storage, without compromising the design.” He concurs: “I have this weird thing where I don’t really like storage, but I’m a hoarder. Every now and again, things just disappear.” It’s his turn to look meaningfully at Susana. They clearly work well together, and are both very relaxed in Little Cottage, barefoot and wearing surfer-shabby clothing. Susana is sitting cross-legged on the floor, outlining the plans for the garage conversion to the builder, while Alex gazes out at the sea and talks about the future.

While the private residences challenge his creativity – recent projects include a magical adobe-walled mansion, slightly sunken and set into a remote Kenyan landscape, as well as a cool new restaurant in Hong Kong – he is also pushing to develop another arm of the business, called Demo Space. Michaelis Boyd, Alex explains, is frequently approached by clients to renovate grand, often semi-derelict buildings. It can be many months or even years before the architect plans are approved, and in that time, the buildings lie empty, at risk of being squatted, suffering decay or infestation.

It seems wrong to Alex that these often exquisite buildings are lying empty, wasted, so he hit upon the idea of taking the building off the client’s hands and making use of it in the interim time. While he won’t go into detail – the Demo Space business officially launches in September this year – it clearly fits with his belief that relevant diversification is the key to staying afloat, and thriving in what is a highly unpredictable property market.

michaelisboyd.com