Clothes with Conscience

Clothes have never been so cheap. Those of us who grew up in the 70s and 80s remember clothes that lasted until they literally wore out. Jumble sales were de rigueur and most mums still sewed up holes in jumpers and put patches on trousers. Now, you can buy an elegant dress from Primark for £8, wear it a few times and chuck it out. Those with a social conscience might take it to the charity shop or recycle it. Others will just bin it and let it go to landfill.

The fashion industry is booming, but as with all rapid growth, there is fallout. From the sourcing of the raw materials, right through the supply chain to the waste at the other end, we are slowly becoming aware of the impact our over-consumption is having. Behind much of that growing awareness is a global activist organisation: Fashion Revolution. With over 100 members in countries all over the world, Fashion Revolution is dedicated to waking us up to the world of fashion, working to alter the behaviour of retailers, consumers and policymakers everywhere to make the supply chain more transparent, better regulated and healthier for the planet.

The organisation was the brainchild of Carry Somers, who literally had a eureka moment in the bath. Back in 2013, the Rana Plaza garment factory in Bangladesh collapsed, killing over 1,000 workers and injuring over 2,000. The factory, like so many others in Bangladesh and in developing countries around the world, supplied major high street brands, from Benetton to Walmart and from Monsoon to Primark. It sent out shock waves and highlighted to the public the conditions in which their clothes were being made. For those in the fashion industry, like Carry Somers, it was no surprise at all. Having been running an ethical clothing business for close to two decades, she had been quietly promoting better transparency with her products. But after the factory disaster, she knew that it was time to wake people up.

A few days after the event, Carry was in the bath when the idea of Fashion Revolution hit her: “The name, the idea of doing something on the anniversary of the disaster, everything. As an entrepreneur, it was definitely one of those ideas where I knew I had to get out of the bath and do something about it. I could have leaned back and done nothing, and I would have got out of the bath, thinking: ‘interesting idea’, and just done nothing about it.” Instead, she called Orsola de Castro, a fashion maker known as the Upcycling Queen, thanks to her work recreating old garments for high-end fashion brands. Orsola agreed immediately, and they co-founded an activist organisation to try to change the nature of the entire industry.

Carry’s background is one of personal passion and a sense of social responsibility. She grew up in Axmouth in East Devon, with family roots dating back hundreds of years in the bucolic village of Branstone. It is safe to say that she was not exposed to many of life’s iniquities. After studying Languages at Oxford, it was when she went on to do a Masters in Native American studies that she discovered her passion for social anthropology.

Spending time looking at the development of the textile industry in Ecuador, she visited cooperatives which had been subjected to arson attacks because they were trying to cut out the middle man. After completing her Masters, she went back and bought clothing products directly from the cooperatives and designed knitwear for them to produce. “I brought them back to England and they were really popular. I sold out within six weeks. I got another range made, and they sold out really quickly, too.”

Within months, she had quite a lot of people reliant on her – “They had enough money to send their children to school, to pay the education fees. So I decided to carry on with this little fledgling fashion business.” What followed were years of struggle. South America was a dangerous place to be, she admits, and she was robbed of thousands of pounds; she had two death threats, but somehow it made her more determined. She lived in a van and sold her ethically sourced Ecuadorian knitwear and panama hats at events around the South West to pay back the debt, and eventually opened a shop in Gandy Street in Exeter to sell her goods.

Her company, Pachacuti, grew wings, and when the Conran Shop spotted her panama hats at an event, Carry began to have an impact in the fashion industry. The ethical hats appeared on catwalks around the world and were sold internationally. Pachacuti became a brand that was synonymous with fair trade. But at the time, Carry was just a small voice in a big industry that was (and still is) hell-bent on production and consumption – unchecked and unbridled.

It is now five years since Fashion Revolution sprang out of the bathwater. In that time, it has become recognised as the world’s largest fashion activist movement. Fashion Revolution Day – a day of awareness-raising on the anniversary of the Rana Plaza disaster – became Fashion Revolution Week, and last year, one million people in over 1,000 countries around the world engaged with the events. It is a huge undertaking. Once Carry and Orsola started raising awareness about the conditions for garment producers, they realised that they couldn’t ignore all the other iniquities in the fashion industry – from gender imbalance to the environmental impact of our clothing, from child labour to chemical- related health issues for the consumer.

It is privately funded – often through collaborations with other NGOs such as Greenpeace – and through organisations and corporations in the fashion industry, most notably C&A, the Dutch clothing company which has become dedicated to improving all elements of the industry. There are only four full-time and five part- time people working in the London HQ, but there are 100 Fashion Revolution coordinators around the world, many of whom have applied for NGO status.

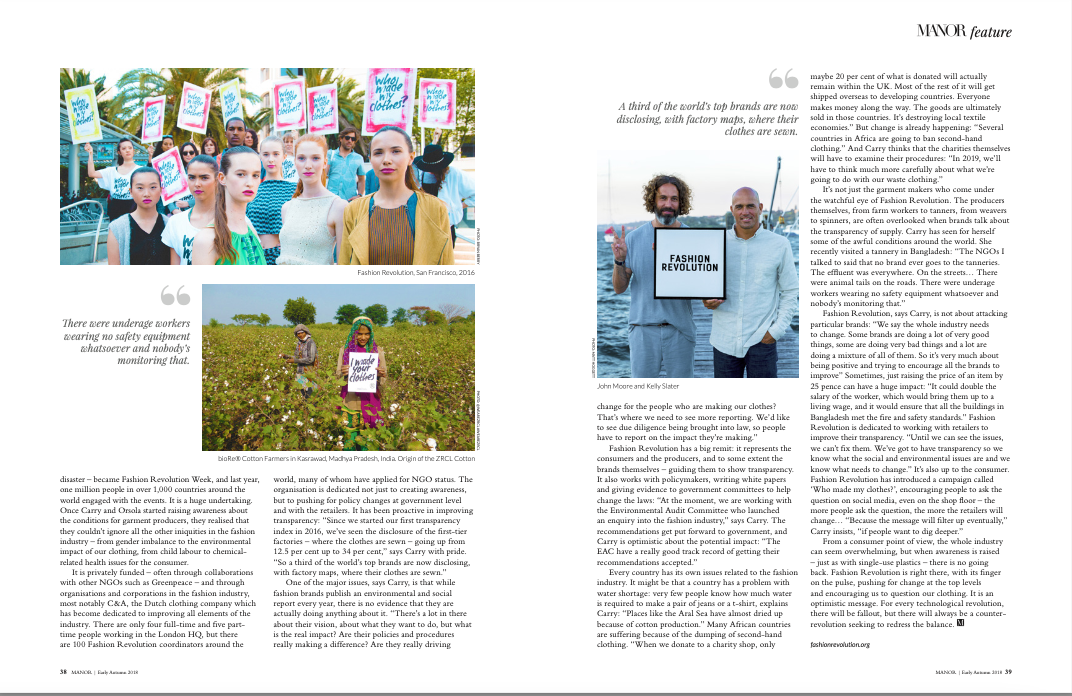

The organisation is dedicated not just to creating awareness, but to pushing for policy changes at government level and with the retailers. It has been proactive in improving transparency: “Since we started our first transparency index in 2016, we’ve seen the disclosure of the first-tier factories – where the clothes are sewn – going up from 12.5 per cent up to 34 per cent,” says Carry with pride. “So a third of the world’s top brands are now disclosing, with factory maps, where their clothes are sewn.”

One of the major issues, says Carry, is that while fashion brands publish an environmental and social report every year, there is no evidence that they are actually doing anything about it. “There’s a lot in there about their vision, about what they want to do, but what is the real impact? Are their policies and procedures really making a difference? Are they really driving change for the people who are making our clothes? That’s where we need to see more reporting. We’d like to see due diligence being brought into law, so people have to report on the impact they’re making.”

Fashion Revolution has a big remit: it represents the consumers and the producers, and to some extent the brands themselves – guiding them to show transparency. It also works with policymakers, writing white papers and giving evidence to government committees to help change the laws: “At the moment, we are working with the Environmental Audit Committee who launched an enquiry into the fashion industry,” says Carry. The recommendations get put forward to government, and Carry is optimistic about the potential impact: “The EAC have a really good track record of getting their recommendations accepted.”

Every country has its own issues related to the fashion industry. It might be that a country has a problem with water shortage: very few people know how much water is required to make a pair of jeans or a t-shirt, explains Carry: “Places like the Aral Sea have almost dried up because of cotton production.” Many African countries are suffering because of the dumping of second-hand clothing.

“When we donate to a charity shop, only maybe 20 per cent of what is donated will actually remain within the UK. Most of the rest of it will get shipped overseas to developing countries. Everyone makes money along the way. The goods are ultimately sold in those countries. It’s destroying local textile economies.” But change is already happening: “Several countries in Africa are going to ban second-hand clothing.” And Carry thinks that the charities themselves will have to examine their procedures: “In 2019, we’ll have to think much more carefully about what we’re going to do with our waste clothing.”

It’s not just the garment makers who come under the watchful eye of Fashion Revolution. The producers themselves, from farm workers to tanners, from weavers to spinners, are often overlooked when brands talk about the transparency of supply. Carry has seen for herself some of the awful conditions around the world. She recently visited a tannery in Bangladesh: “The NGOs I talked to said that no brand ever goes to the tanneries. The effluent was everywhere. On the streets... There were animal tails on the roads. There were underage workers wearing no safety equipment whatsoever and nobody’s monitoring that.”

Fashion Revolution, says Carry, is not about attacking particular brands: “We say the whole industry needs to change. Some brands are doing a lot of very good things, some are doing very bad things and a lot are doing a mixture of all of them. So it’s very much about being positive and trying to encourage all the brands to improve” Sometimes, just raising the price of an item by 25 pence can have a huge impact: “It could double the salary of the worker, which would bring them up to a living wage, and it would ensure that all the buildings in Bangladesh met the fire and safety standards.”

Fashion Revolution is dedicated to working with retailers to improve their transparency. “Until we can see the issues, we can’t fix them. We’ve got to have transparency so we know what the social and environmental issues are and we know what needs to change.” It’s also up to the consumer. Fashion Revolution has introduced a campaign called ‘Who made my clothes?’, encouraging people to ask the question on social media, even on the shop floor – the more people ask the question, the more the retailers will change... “Because the message will filter up eventually,” Carry insists, “if people want to dig deeper.”

From a consumer point of view, the whole industry can seem overwhelming, but when awareness is raised – just as with single-use plastics – there is no going back. Fashion Revolution is right there, with its finger on the pulse, pushing for change at the top levels and encouraging us to question our clothing. It is an optimistic message. For every technological revolution, there will be fallout, but there will always be a counter- revolution seeking to redress the balance.