Shaping the Future

We’ve all seen the pictures: sepia-tinted images of powerful men in swimming shorts standing next to gigantic surfboards, great planks of wood towering above their heads. These men were the early gods of surfing, hitting giant rollers with 15-foot boards, constructed of redwood drilled with hundreds of holes and finished with thin layers of varnished wood. By the mid-1930s, people began to tinker with the design, shaving the tail to make a more manoeuvrable shape, and introducing super-light balsa wood to coat the tough redwood core. Ten years later, the first fibreglass board was made, with a plastic-based interior. By the 1950s, commercial boards were made from foam with a coating of fibreglass and polyester resins, and surfing has never looked back.

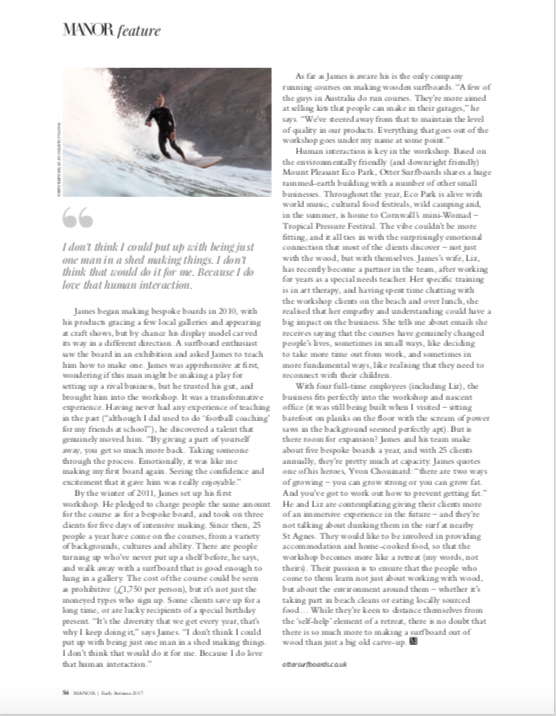

Until now. In a small workshop perched within sight of one of north-west Cornwall’s surf breaks, James Otter is creating wooden boards that are reminiscent, and indeed redolent, of those early versions. Granted, they’re shorter – by quite a lot – and they’re shaped exactly like the modern boards of today, complete with elegantly curved fins and swish tails. They’re made from cedar, poplar and small amounts of hardwood. Like anything created from wood, the distinctive character of each strip, each chunk of offcut shaped into a fin or a design element, gives each board an essence, almost a personality. People buy them as decorative items to hang on a wall or in a gallery, as much as to surf on.

Originally from Buckinghamshire (“about as far from the sea as you can get”), James Otter grew up making things. One grandfather was a carpenter, the other a farmer, and he was drawn to work with them in their respective skills. By the time he was at secondary school, James spent as much time as he could in the Design Technology and Art departments, working on his favourite material – wood. In his early teens, on holidays to Cornwall, he found his other passion: surfing. It influenced his sensitivity to the ocean environment, and his choice of university. Studying Design and Making at Plymouth, and heading towards a career in furniture-making, he hit upon the idea of wooden surfboards. “I was fed up with how foam boards don’t have much of a lifetime,” he says. “I thought I might be able to do something longer-lasting.”

Care for the environment is one of James’s deepest drivers. Once he’d made his first board – using a lattice-like wooden internal framework instead of foam – he replicated the concept in a piece of furniture for his degree, and ended up winning two awards. “I enjoyed the furniture-making,” says James, “but making

the surfboard was a whole other level of enjoyment. Knowing what you were going to be doing with it when it was finished was really inspiring. At that point, I decided that I had to keep doing it.” With the money from the awards, he invested in some machinery, asked a friend in Cornwall to house it in a barn, and set to work building boards. Sourcing sustainable wood with good provenance was paramount. “It’s not just a case of using wood in general,” James yells over the grinding sound of machinery in the workshop. “It’s a case of choosing the people that are working with the wood and growing the wood and harvesting it in a sustainable way.” He found a forester managing a woodland on the Wiltshire-Somerset border who was so passionate about nurturing the trees that the timber was almost a by-product for him.

Almost everyone who works with wood feels some kind of kinship with the material. “From my point of view, using wood is about a connection back to the earth,” James explains, more quietly this time, in a lull between the screech of sawing machines. Working with wood requires an understanding of how it behaves; you need to pay attention all the time – choosing just the right tool for each part of the timber. Pattern and the aesthetics are clearly major selling points for Otter Surfboards, but James sees them as a by-product. What he really cares about is creating a board that has longevity, is harvested from sustainable sources, and doesn’t contribute to the pollution of our planet. Even the resins that are used to seal the boards are ‘bio-resins’, chosen for their non-toxic impact.

James began making bespoke boards in 2010, with his products gracing a few local galleries and appearing at craft shows, but by chance his display model carved its way in a different direction. A surfboard enthusiast saw the board in an exhibition and asked James to teach him how to make one. James was apprehensive at first, wondering if this man might be making a play for

setting up a rival business, but he trusted his gut, and brought him into the workshop. It was a transformative experience. Having never had any experience of teaching in the past (“although I did used to do ‘football coaching’ for my friends at school”), he discovered a talent that genuinely moved him. “By giving a part of yourself away, you get so much more back. Taking someone through the process. Emotionally, it was like me making my first board again. Seeing the confidence and excitement that it gave him was really enjoyable.”

By the winter of 2011, James set up his first workshop. He pledged to charge people the same amount for the course as for a bespoke board, and took on three clients for five days of intensive making. Since then, 25 people a year have come on the courses, from a variety of backgrounds, cultures and ability. There are people turning up who’ve never put up a shelf before, he says, and walk away with a surfboard that is good enough to hang in a gallery. The cost of the course could be seen as prohibitive (£1,750 per person), but it’s not just the moneyed types who sign up. Some clients save up for a long time, or are lucky recipients of a special birthday present. “It’s the diversity that we get every year, that’s why I keep doing it,” says James. “I don’t think I could put up with being just one man in a shed making things. I don’t think that would do it for me. Because I do love that human interaction.”

As far as James is aware his is the only company running courses on making wooden surfboards. “A few of the guys in Australia do run courses. They’re more aimed at selling kits that people can make in their garages,” he says. “We’ve steered away from that to maintain the level of quality in our products. Everything that goes out of the workshop goes under my name at some point.”

Human interaction is key in the workshop. Based on the environmentally friendly (and downright friendly) Mount Pleasant Eco Park, Otter Surfboards shares a huge rammed-earth building with a number of other small businesses. Throughout the year, Eco Park is alive with world music, cultural food festivals, wild camping and, in the summer, is home to Cornwall’s mini-Womad – Tropical Pressure Festival. The vibe couldn’t be more fitting, and it all ties in with the surprisingly emotional connection that most of the clients discover – not just with the wood, but with themselves. James’s wife, Liz, has recently become a partner in the team, after working for years as a special needs teacher. Her specific training is in art therapy, and having spent time chatting with the workshop clients on the beach and over lunch, she realised that her empathy and understanding could have a big impact on the business. She tells me about emails she receives saying that the courses have genuinely changed people’s lives, sometimes in small ways, like deciding to take more time out from work, and sometimes in more fundamental ways, like realising that they need to reconnect with their children.

With four full-time employees (including Liz), the business fits perfectly into the workshop and nascent office (it was still being built when I visited – sitting barefoot on planks on the floor with the scream of power saws in the background seemed perfectly apt). But is there room for expansion? James and his team make about five bespoke boards a year, and with 25 clients annually, they’re pretty much at capacity. James quotes one of his heroes, Yvon Chouinard: “there are two ways of growing – you can grow strong or you can grow fat. And you’ve got to work out how to prevent getting fat.” He and Liz are contemplating giving their clients more of an immersive experience in the future – and they’re not talking about dunking them in the surf at nearby St Agnes. They would like to be involved in providing accommodation and home-cooked food, so that the workshop becomes more like a retreat (my words, not theirs). Their passion is to ensure that the people who come to them learn not just about working with wood, but about the environment around them – whether it’s taking part in beach cleans or eating locally sourced food... While they’re keen to distance themselves from the ‘self-help’ element of a retreat, there is no doubt that there is so much more to making a surfboard out of wood than just a big old carve-up.

ottersurfboards.co.uk