Green Credentials

Low energy. Sustainable. Natural materials. Low water usage. Community driven. Diverse. Is this the future of our built environment?

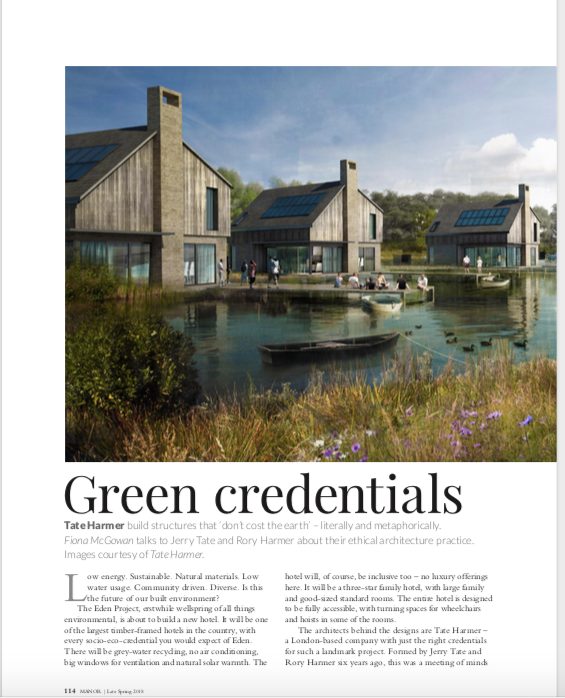

The Eden Project, erstwhile wellspring of all things environmental, is about to build a new hotel. It will be one of the largest timber-framed hotels in the country, with every socio-eco-credential you would expect of Eden. There will be grey-water recycling, no air conditioning, big windows for ventilation and natural solar warmth. The hotel will, of course, be inclusive too – no luxury offerings here. It will be a three-star family hotel, with large family and good-sized standard rooms. The entire hotel is designed to be fully accessible, with turning spaces for wheelchairs and hoists in some of the rooms.

The architects behind the designs are Tate Harmer – a London-based company with just the right credentials for such a landmark project. Formed by Jerry Tate and Rory Harmer six years ago, this was a meeting of minds and experience. Jerry’s background could hardly have been more suited to this venture. Having been taught by the now-legendary Robert and Brenda Vale, Jerry was impassioned by their idea of the ‘autonomous house’ – a residential building that required no heating or cooling.

Soon after graduating, Jerry secured a job at Grimshaw Architects. His first work with them was to help create the Eden Project. It was an inspiring time, he says – he spent eight years working on the site, and the timber-framed Core building with its petal-like copper roof was his pet project. What visitors might not know is quite how sustainable the Core’s materials are: the flooring is variously made from flax and maize, the green tiles from recycled beer bottles, and the timber is recycled or sourced from sustainable woodland. It is no surprise that, after this formative experience working with such a client, when Jerry began his own practice, his focus was firmly on sustainability and inclusivity.

Rory Harmer’s background was no less environmentally driven. Having worked at Farrells architecture firm – known for its large-scale projects aimed at improving the urban environment, both socially and environmentally – he met Jerry while studying for his masters at UCL’s Bartlett College, where Jerry was teaching. Soon afterwards, they formed Tate Harmer, and have taken on a wide range of projects – from one- off residential designs to visitor attractions, hotels and creating blueprints for houses to be incorporated into larger development schemes. Running through it all is a commitment to their ethics.

“No matter what the size of the project, we are keeping the same ethos of low-energy, sustainable buildings – buildings that are easy to use,” says Rory. Their focus is on simplicity – using the landscape and siting to help keep down energy costs. Their plans usually revolve around elements as seemingly obvious as using windows for ventilation and sunlight to warm and light the house. They have built a number of ‘Passivhaus’ buildings – the autonomous house concept much loved by the Vales – most notably Hoo House in Suffolk, which featured in Grand Designs. The house looks the height of luxury, designed to be airy and open, with a sweeping apex of a roof and masses of natural light flooding down from a wide strip of roof light sandwiched between steep gables. The extensive concrete flooring means the house requires no heating or cooling. Thanks to recycling, water use is minimal. Incredibly, the cost of the build was on a par with that of any ‘ordinary’ house (architects’ costs aside, presumably).

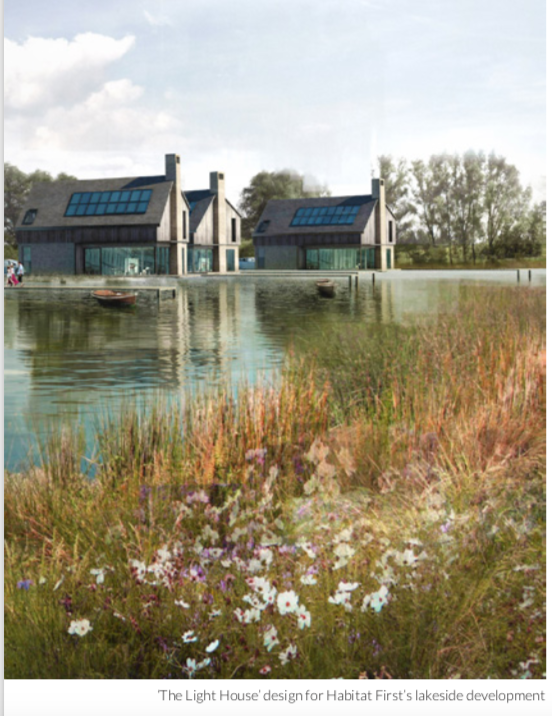

Using Hoo House as a basis, Tate Harmer were approached by Habitat First Group to design a typical detached Passivhaus that could be replicated throughout their developments of lakeside holiday communities (think an upmarket Center Parcs, gone green) in Somerset and Dorset. Named ‘The Light House’ – “because it would bring a light touch to the landscape and because of its energy consumption,” elucidates

Rory – it is built using prefabricated, super-insulated timber panels that can be easily erected on-site. “We can normally put these houses up in a few weeks,” he adds.

Although working for these clients is serving a very specific market, Jerry believes that this concept could be upscaled to the mass-housing market. “I genuinely think that this could be a model for the future of residential living,” he enthuses. “That market is quite often reasonably conservative – it takes a while for contemporary eco-houses to reach the mass market. The truth is, I could build you a house, right now, with the same cost criteria as the mass-produced houses, and it would be timber-framed, lovely to live in and use less energy – a much better house from a contemporary eco- sustainable point of view.”

Moving things forward in the housing market can be like running through treacle – and it gets Jerry quite fired up: “I can’t stand the fact that housing hasn’t delivered that yet. But we’re not ready to give up on it.” The practice is designing community-focused eco- flats in Croydon, 69 units in Norfolk, and there are plans for a groundbreaking housing scheme in West Carclaze, not far from the Eden Project in Cornwall. The latter, spearheaded by developers EcoBos, is an ambitious proposal to provide 5,000 affordable homes to a financially depressed part of Cornwall, complete with a biodiverse environment and ultra-low-energy houses. Needless to say, it has been stultified by planning red tape and a complex mix of support and resistance from local councils. Jerry says it is still moving forward, albeit painfully slowly, and some pre-emptive highways infrastructure has been built in readiness.

For a practice with only 12 employees, Tate Harmer has an impressive range of projects, all of which feed more knowledge and skills back into the practice.

In 2015, they created the rather dinky ‘tree office’ built for Hackney council – a transparent, biome-like office space erected in Hoxton Square to generate enough income to pay for the upkeep of the park. “We experimented with putting water in the transparent roof cushions to create a ‘phase change’ cooling device,” explains Rory. “As the heat of the sun hit the cushion, it would heat up the water, turn it to vapour and the condensation evaporation would help cool the space below.” Building the canopy walkway in the rainforest biome drove more innovative solutions in terms of building close to a natural environment: “We made it out of lots of little bits, so we didn’t affect the vegetation as we put it up,” says Rory. “We developed new construction techniques that allow you to do things like inserting houses around trees.”

Everything they do is focused on the intersection of the social and physical environment: whether it’s the eye-catching Brunel Museum in Rotherhithe (Isambard’s first building, now converted into a performance space and accessible museum over six levels) or the plans for the new Museum of Scouting in Chingford (combining

a museum with a space capable of handling 5,000 active young people). It will feature a glorious multicoloured tent/ awning and a great big wooden tower, says Jerry: “It’s got to be exciting and fun; it has to provide physical activities and access to landscape...” And Rory adds: “But you still have to make them aware of their rich and diverse heritage.”

Architecture, says Jerry Tate, is exciting when there’s a big problem and a big challenge. “The Industrial Revolution provoked massive change, as did the introduction of mass production in the twentieth century. Today, our issue is that we need to treat the Earth with more respect.” Both he and Rory teach architecture at UCL Bartlett, and while they are keen to pass on their understanding to the next generation, they are encouraged to see a positive trend among the students: “There’s a real move to care more about your impact socially and environmentally than about your personal gain,” says Jerry. “Rather than the pure architecture, there’s more talk about the broad environmental or socio-political impact – what buildings can do.”

As architects, Rory says, they have to be conscious of their long-term impact. “You also want to make sure that your legacy – the buildings you leave behind as an architect – reflects well on you. You don’t want to have these energy-guzzling buildings. We have a responsibility to leave the planet in a better state than we found it.”

tateharmer.com