Healthy Habitats

Imagine living in a house that is so well insulated that it hardly needs to be heated. That is so well ventilated that its very walls breathe. That never gets condensation, or mould, or excess dust. Whose very fabric is built from simple materials with no toxic chemicals, no plastics.

Imagine a house that is designed to keep electrical currents away from you as you sleep. Now imagine that this house looks like any other home, and costs only marginally more to build than your average Barratt-box new build. Does that sound appealing? Of course it does.

This is the premise of a movement of construction design called Building Biology. These days, energy efficiency is the buzzword for any new build, and the government has introduced strict assessment systems to ensure that anyone who buys or rents a house can see the energy efficiency of their home before they decide to live in it. Building standards are now way better than they ever were in terms of insulation and environmental design. But, says David Gale, co-founder of Exeter-based architectural practice Gale & Snowden, modern buildings are actually becoming more toxic to live in. Building regulations do not give much attention to the materials that are being used in builds and refits. While we may not realise the harm these things are doing to us, there will no doubt be fallout in years to come. “We knew that asbestos was dangerous to health as far back as 1900,” says David, “but it was only banned from use in 1999.” The problem is, of course, that many of the damaging effects of our surroundings are not immediately obvious. Where the cause and effect aren’t right in our faces, we are particularly good at looking away. “It is an unfortunate trait of human beings – we tend to wait until disaster happens before we do anything,” says David. Whether it’s seatbelts, smoking or fire regulations – all of them required years of medical evidence and major crises before anything was put into legislation.

Gale & Snowden is one of the few practices in the UK which is trying to change our very habitats before a crisis happens. It’s an uphill battle.

David grew up on the North Devon coast – living in Barnstaple, his family had a holiday cottage in the coastal hamlet of Bucks Mills. He was imbued with the nature around this place – a deep, steep wooded chine whose rushing stream gives out into a small, stony beach. He was drawn towards Marine Biology and started out on a Biological Sciences degree, but quickly discovered that the ‘chemistry for industry’-orientated course wasn’t for him. He wanted to blend arts with science... and shifted into architecture. But this again didn’t satisfy his interest in nature: “After going through the seven-year course of architecture,” he says, “the penny dropped and I realised I’d done the wrong thing. I should have remained a biologist. Because these architects were doing things that were polluting the environment and being totally unhealthy for people.”

Working in architecture, he soon realised that most building developments were driven by money and resulted in “a lot of faceless, not very nice buildings made mostly of plastic”. In 1990, he had a short, but eye- opening, stint with a firm based in Colchester, where he met (practice co-founder) Ian Snowden, and where “we were doing the first timber-framed vapour-permeable buildings in the Finnish style, where you are allowing moisture to migrate through natural materials and using recycled newspaper for insulation”. While the use of natural materials is becoming much more mainstream today, this was pioneering stuff at the time, and the firm failed to succeed: “It was all social housing. But Margaret Thatcher pulled the plug on social housing and suddenly we didn’t have any work.” Ian and David were made redundant, and David retreated to Devon, disheartened.

Before hunkering down in the cottage at Bucks Mills, he did a permaculture course. Permaculture, explains David, is the process of designing the natural environment for people to be part of. It is beautiful in its simplicity. It’s about making all our inputs and outputs part of the environment around us. And no, that doesn’t mean making a Ray Mears-style lean-to in the woods and pooing in little holes around your clearing. The idea is to build homes and grow food and use the resources in a way that is part of an ecosystem. Turning his back on the world of architecture for a time, David dedicated his time to making the family cottage a permaculture system of its own. “I became a hermit,” he admits. “I was catching my own fish. I was planting my own food. I was growing a woodland garden – it’s now one of the oldest forest gardens in the country. I renovated my own building and did all the landscaping myself.” There’s nothing like cutting your teeth on the sharp end of building design.

Today, says David, Gale & Snowden acts as much a healthy building consultancy as an architecture firm. The staff of nine are all trained in eco-builds: most of them are Passivhaus-certified and have done the Building Biology course. They work with landscape architects and a species consultant who is also a permaculture expert. “We never wanted to be an architect’s practice,” says David, “We wanted to be more of a permaculture consulting practice, which is much more broad ranging. But we do more architecture, because I think it’s easier for people to know what we do.” And because most of the income for the practice comes from the architecture.

Since Ian Snowden and David joined forces in 1992, their projects have been as wide ranging as you would expect from such passionate proponents in

the field of eco-builds and healthy housing. One of their first clients employed them to create an entire permaculture system at his stately home in Surrey – an inspiring scheme in which all of the natural waste from the house was re-routed back into the landscape, so that grey water went through a system of ponds and reedbeds to provide nutrients for freshwater mussels and edible plants, before being filtered back into the house and reused. Other clients have employed the team to retro-design their homes to make them non-toxic and eco-friendly, with Passivhaus designs to enable even old listed buildings to cost a fraction to heat and provide ultra-natural comfort.

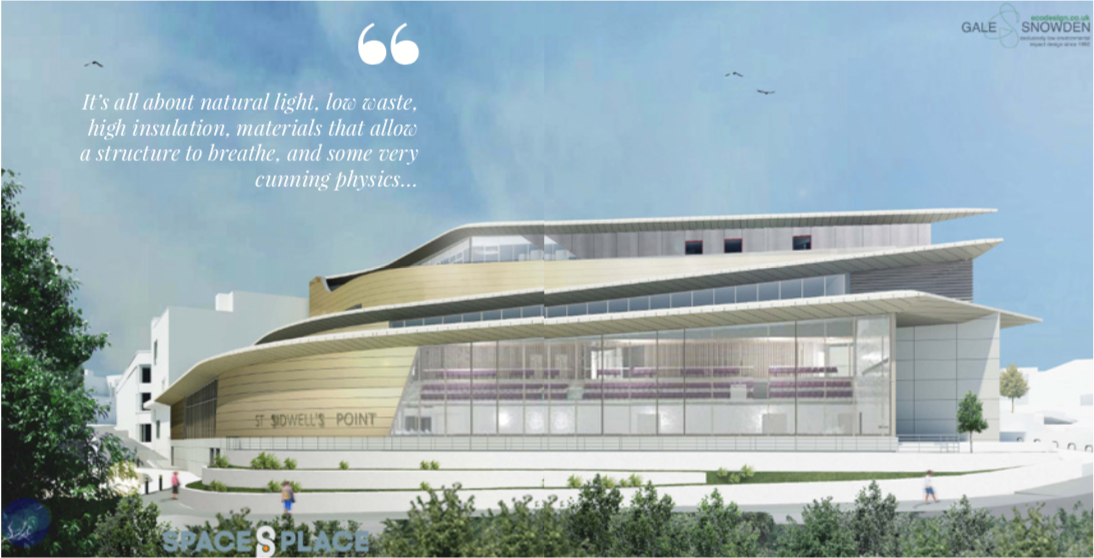

While private clients are vital not just for income – and for providing the wow factor in a portfolio – you get the sense that it is the social side of things that holds the greatest pull for the practice. Over the years, Gale & Snowden has designed village halls, leisure facilities and schools all with the Passivhaus and Building Biology principles. It’s all about natural light, low waste, high insulation, materials that allow a structure to breathe, and some very cunning physics to do with balancing out the mass of the fabric to the space and the amount of energy that can be reused within the building to make them self-heating and self-cooling.

Recently, Gale & Snowden has been working with Bournemouth Town Council to build social housing that makes use of big, aerated clay blocks. The buildings do not need any insulation, says David: “There’s no actual insulation other than the holes in the clay and this allows a vapour-permeable structure – because it’s a natural material, moisture can migrate through them.” The blocks absorb moisture to prevent the inside from becoming too humid, and release moisture when the internal atmosphere is too dry. There are recently completed projects with Bristol City Council and Exeter City Council to build social housing. The latest scheme is to build a state-of- the-art Passivhaus leisure centre in Exeter. Working in collaboration with AFLS+P Architects, the designers of the 2012 London Olympic pool complex, and ARUP, Gale & Snowden has been commissioned to make this the world’s first healthy building leisure centre. “The building should use 70 per cent less energy than a normal leisure centre. And 50 per cent less water,” attests David.

As with so many architects, it is their home which showcases their best design principles. David and wife Maria’s house in Bucks Mills is no exception. The original thick-walled, centuries-old cottage sits right next to a rocky, overgrown cliff. An extension, a garage/home office, massive cliff-like retaining walls and a new summer-house space look as though they have been carved into – and carved out of – the cliff. The walls are indeed made from pieces of rock that have been broken off the cliff and put together in the style of a dry-stone wall. Chickens putter about in the yard, which will soon be home to fruit trees, vegetables and edible plants. The walls of the new-builds contain tiny water pipes which thread through the plaster boards, feeding hot water from the heated water tank, which in turn is heated by the Aga. David explains in scientific detail about the benefits of heated walls and floor versus the convection heat from radiators. In simplistic terms, convection heat circulates in the room in a constant stream of heat, which creates warm and cold patches. It also causes dust to circulate. Heating the walls and floors prevents condensation from forming (no mass of cold surfaces) and creates a uniform ambient heat. This makes the room feel warmer, which means you don’t have to turn the heating up so high. The bedrooms have been designed so that electrical currents can be completely switched off at night – negating the effects of electro-magnetic radiation which affect our cells as they regenerate during sleep. The bathroom has a natural ventilation system that involves some sort of flappy valve that expands and shrinks according to the amount of heat and moisture generated.

In the courtyard garden (paved with stone from the cliff, of course) is an outdoor kitchen with a Big Green Egg cooker/smoker/barbecue, sheltered beneath a great oak atrium – whose structure is held together, Amish style, with wooden pegs and clever physics. David and his colleagues (“We all work as one team at Gale & Snowden, and I never want to take the credit for everyone else’s hard work”) are clearly ardent enthusiasts about every element of healthy building construction. To such a degree that David has funded and runs the only Building Biology course in the UK. While it is an online course, he offers seminars and practical sessions looking at healthy buildings the Gale & Snowden team have constructed. They encourage all their clients to take the course, so that they understand exactly why this type of construction is so vital – not just for the future of the planet, but for the long-term health of the residents. With local councillors and social housing developers invited to the courses, it seems as though the message is filtering through – certainly in the West Country.

Improving the way we live on the Earth is always going to be a fight, especially in our use-it-now-sod-the- consequences Western lifestyles. It is the likes of Gale & Snowden that are part of a quiet revolution which might just make a difference to our future as a species.

Gale & Snowden: ecodesign.co.uk