Protect and Preserve

When Brazil is in trouble, the world is in trouble. Just as the parks of London are known as the lungs of the city, the Amazon rainforest is not just the lungs of the world, it is the very thing that could slow climate change as it goose-steps towards us in double-time. Brazil’s new president has vowed to remove the rights of the indigenous people in the rainforest and sell off large tracts of it to mining, agriculture and hydro-power. Within weeks of taking office, he is already exhorting his government to remove controls that protect the rainforest. And there’s precious little anyone can do about it.

It is partly for this reason that environmentalists are desperately seeking ways to preserve rainforests elsewhere in the world. Peru is also home to Amazon rainforest: a massive 60 per cent of its land is covered in tropical forest – all threatened by illegal logging, oil prospecting/ mining and gold mining. The rainforests of Central Africa are equally threatened – especially in the war-torn countries of Democratic Republic of Congo and Central African Republic as well as neighbouring Cameroon. In Asia, Indonesia and Malaysia have been farming palm oil and logging for so long that much of the rainforest has already been destroyed; but there are other areas such as in Cambodia and Papua New Guinea where forest is still standing – and still in desperate need of protection. It is so easy to feel hopeless when faced with the catastrophic results of deforestation and increased carbon emissions, but the fight is still real and the challenges are still being faced by NGOs all over the world.

One such organisation is Cool Earth. Set up in 2007 and based in Falmouth, its remit is to help indigenous communities around the world find a way to strengthen their claim on their home. Ridiculous as it may seem, it is very easy for these people to have their homes literally cut from under their feet. Legally or illegally, prospectors can offer money to communities and begin the work of building cattle ranches or logging or mining or crop farming. Cool Earth helps to support communities to find their own way to subsist without destroying the forest around them. It is a Jacob’s Ladder of a challenge. For every solution, another problem arises. Introduce a system in one small community in Peru, and there’s

no guarantee that it will work 200 miles away in the same country, let alone in the Congo or Papua New Guinea. Matthew Owen, director of Cool Earth since

its inception, is deeply aware of these struggles, and has spent the last 10 years working with his team to come up with practical solutions to each issue.

One of the biggest changes in the last decade, he says, is that those massive swathes of cleared rainforest which once made way for ranches, soya crop farming and logging are now less of a problem: “Today, areas that are under a quarter of a square kilometre account for 70-80 per cent of all deforestation,” he explains. “So we’ve gone from industrial-scale clearing of forest to a far smaller-scale process. It still adds up to huge amounts of forest, but we need very different ways to address it.” There are many reasons for this change, says Matthew – partly because government crackdowns on large-scale clear-cutting has forced it underground, with smaller, illegal plantations and logging enterprises coming into force. Another issue is that many rainforests are in post-conflict areas, where populations are experiencing baby booms and now require more land for growing crops. The vast majority of rainforest communities create a livelihood by carrying out ‘slash and burn’ agriculture techniques. But, says Matthew, “If you clear the forest like that, the growing material disappears very quickly and becomes, if not infertile, then very low productive farmland, which is why slash and burn leads to a cycle of more and more clearance.”

Add to that the fact that the most inaccessible areas of the world are becoming more and more connected, with roads being built to serve remote communities. These then open up huge areas of previously untouched forest to prospectors keen to take advantage of the prized hardwoods, oil or mineral-rich land, and agricultural opportunities... The problems facing the rainforests can seem unsurmountable.

But Cool Earth and other international charities are doing their best to solve the problems, one patch at a time. The Falmouth-based NGO has around 20 employees in the UK and double that on the payroll in the countries in which they work. Their solutions are both simple in concept and complex in application. The basic idea is that they help to fund communities to protect their own backyards. Much of it is about learning which solutions work and which don’t. Their billionaire founder once bought 400,000 acres of rainforest in Brazil with the intention of protecting it from logging. While this idea didn’t work very effectively – he faced accusations of ‘green colonialism’ from the Brazilian government – it did lead him to set up Cool Earth to try to find alternative ways to protect the forest.

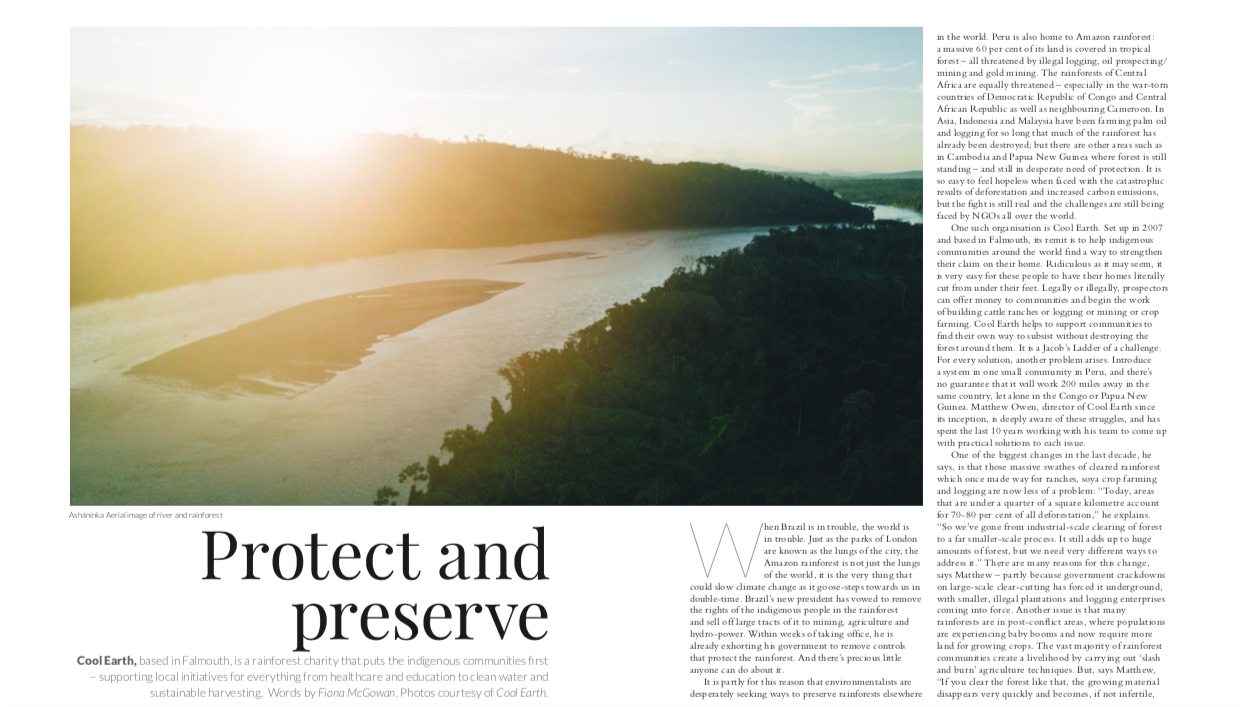

After years of working on the ground, says Matthew, the organisation has discovered that: “It’s not about taking control and ownership, it’s making sure that you can provide alternatives to the illegal logging or the aggressive slash and burn so that people can still feed their families.” One model was to use funds from donors to outbid the loggers – offering a long-term investment to the local community association in return for them managing and monitoring the forest around them. It was highly successful with the Asháninka and other remote communities in Peru. Many of their ideas, he says, are both scalable and applicable to other rainforest communities around the world. However, in Papua New Guinea, that particular funding system fell down dramatically. There were problems with powerful leaders making decisions that only benefited their families. In the end, Cool Earth found that giving exactly the same parcels of money to every single family with the proviso that each looked after their patch of forest worked pretty successfully.

Because the problems facing the rainforest are so varied, it has led to the development of a huge array of NGOs – from the small local ones to the massive international ones – each tackling the issues in their own ways. Matthew is keen to emphasise that Cool Earth is all about collaboration, working for the most part

with indigenous people and local charities. “We’re very keen on ensuring that we don’t adopt the white saviour mentality – just arriving there on the forest floor with a whole bunch of solutions for everyone’s problems, which never really work.” He expands: “Instead, we provide resources for people to understand the issues. If they take them up or if they don’t, it’s entirely up to them. If someone needs to be trained in our suggested solutions, we don’t send one of our team from Cornwall – we’ll send, for example, people from Peru to Honduras, where they can learn exactly what works there and what doesn’t work. We’ll then do an exchange between different communities within Peru itself.”

Cool Earth is dedicated to helping communities become self-sufficient so that, after a few years of support, they are no longer dependent on the charity. This might mean encouraging them to introduce sustainable agriculture and helping them to set up networks for export. How, you might ask, do you encourage agriculture without cutting down the forest? Cool Earth works with another Cornwall-based charity, the Inga Foundation, to show that planting alleys with small trees called Inga trees can provide shelter for crops to be grown without the need to cut and burn large areas of forest. The ‘alleyways’ are sustainable and can be re- planted year after year.

While it is important to change legislation at national and international level, it is the very remoteness of the world’s rainforests that makes them particularly vulnerable to illegal logging. So even if the international furore about palm oil and unsustainable hardwoods leads to local governments putting in rules, it is incredibly hard to monitor and enforce these laws. For every seemingly hopeless situation, though, there is the tenacious work of NGOs to find solutions. Matthew says that the development of AI and surveillance technology can help not only governments, but charities like Cool Earth to see where some of the flashpoints might be, and where they need to support the local communities to fight corruption and illegal logging. Partnering with academics has been key: “We’re working with universities in Exeter, Cambridge and Melbourne,” he says. “My last meeting was with the University of Oxford’s and some smart techy businesses – like Planet Labs, who have designed some of the most advanced mini satellites who fly in flocks of 40 or 50 to give you a cloud of images pretty much 24 hours a day.”

Cool Earth is much smaller than many of the other rainforest charities, with arguably less visibility than the likes of the Rainforest Foundation, but their advantage is that they are more flexible in their approach. Matthew explains that while bigger NGOs have separate departments for funding, research, marketing and operations, Cool Earth has a more fluid structure: “We usually hire people from academia, or the private sector, because then our team doesn’t just follow the playbook that charities have been doing for decades – they think

of the problem anew and figure out different ways of approaching it.”

Rainforests are as vital to halting climate change as reducing our carbon emissions, and the work of charities that are protecting them is intrinsic to our survival. And from an office on the Falmouth University campus, Cool Earth is not just protecting the forests and their ecosystems but saving communities and their ways of life. “I think,” says Matthew thoughtfully, “what Cool Earth is trying to do is absolutely critical to the equation of addressing climate change. All we can do is keep the forests standing while politicians continue to talk.”

coolearth.org