Sea Life

There’s a group of islands in the Indian Ocean nearly 1,000km south of the Maldives and 2,000km east of the Seychelles. They are palm-fringed, white- sanded atolls sitting in pristine turquoise waters that drop away to teeming coral reefs and the inky depths of ocean. They are uninhabited, and the area around the archipelago is the world’s largest marine conservation area: 544,000 sq km of Oceanic Preservation and Protection Zone, where fishing is banned. It is here that a team of conservation experts monitors and analyses an untouched realm of sea-life. One of the people diving with the team is marine biologist Heather Koldewey – the head of global conservation for the Zoological Society of London (ZSL), and one of the world’s most highly respected individuals in marine conservation.

That Heather manages to combine this job – the impact of which reaches, tentacle-like, around the world – with a family life in Marazion, Cornwall, is a miracle to me. As we sit in a huge bay window at the Godolphin Arms, overlooking a beach scattered with children from the local school, and dominated by the iconic castle of St Michael’s Mount, Heather charts her journey to this point. “My children go to that school,” she says, smiling. “They go to the beach all the time. And see that kite out there?” She points to the bright parabola of a kite-surf sail racing across Mount’s Bay. “That’s my husband, teaching kite surfing.”

What looks like perfection on this sunny autumn day is, of course, no easy coast. Heather works two days a week in London, and when she’s at home, often has to work all hours of the day and late into the night because of the time-zone differences between ZSL’s HQ and all of its outposts around the world. The children – aged eight and five – often beg for Mummy to stay at home. Journeying to the Philippines for three-week stints twice a year, with intermittent trips to Chagos and various conferences and work around the world, is gruelling. The payoff, however, is tremendous: diving on coral reefs in tropical oceans, spending time working with ZSL teams. “We employ local people for all of our bases overseas,” she explains, as well as working to educate and influence governments in protecting their coastlines and oceans.

It’s incredible to think that this all started with a lot of stomping around the Welsh countryside in wellies, studying the genetics of river trout. As a child, Heather lived all around the world – a “military brat”, as she puts it – until she was about 12, when her parents bought a small farm near Bideford in Devon. “I’m definitely a Westcountry girl,” she says, enthusing about a youth spent rockpooling, windsurfing, diving and horse-riding. Her passion for animals and wildlife led her to imagine becoming a vet, “but I didn’t get the grades,” she explains. It was a good thing she didn’t – those grades led her into a Biological Sciences degree, which inexorably led to the role she now holds: as a highly influential figure in global conservation.

With a PhD in Welsh trout genetics (“it’s quite niche”), Dr Koldewey had a deep understanding of conservation. Stomping around in wellies was clearly natural for a girl brought up on a farm, but it was examining the effect of decades of mining pollution on fish populations in the Welsh rivers, and working closely with locals on a management plan for re- stocking rivers that set her up for the future. Her job was as much about empathy and searching for solutions to man-made problems as it was about doing genetic analyses in the lab.

While working as a post-doc geneticist at the Institute of Zoology in London (the academic arm of ZSL), she heard about a job running the reptile house and aquarium at London Zoo. “I was sharing an office with a bat researcher, and she bet me a bottle of wine that I wouldn’t get the job.” She was amazed to be offered the position. She was young, female, inexperienced and, by her own admission, naive. “It was unusual having a scientist going into management – that was a real challenge for me,” she says. Not least because she was in charge of keepers who had been working there for decades. She was tested at every step of the way – from having a snake thrust into her hands by one keeper – “Of course I wasn’t scared” – to being in charge of the entire zoo every third weekend: “We had to be prepared for an animal to escape. I was a trout geneticist, and I was planning a scenario of what to do if a tiger gets out.” Luckily, a background of helping her mum on the farm, working with tough Welsh countryside bailiffs, and her personality – “I’m very stubborn” – enabled her to create a role for herself and develop an elite team of conservation-focused staff.

Her youth and drive enabled her to push for more conservation awareness in the aquarium side of things, and she went on to spearhead ZSL projects

all around the world, saving marine and freshwater fish from extinction in locations as diverse as Mexico and the Philippines. It was the little seahorse that was instrumental in globalising Heather’s focus. Millions of these creatures are traded around the world every year, sold to aquariums or as dried trinkets. In 1996, Heather worked with a team to unravel the myriad genetic types of seahorse, then set up breeding programmes which have since been adopted as part of a Europe-wide initiative.

“Part of my job was conservation,” says Heather, “and I had the freedom to pick what I wanted to save. I thought – I’ve been stomping around really cold rivers for so long, let’s see where I can go that’s a bit warmer.” Seahorses are found in waters all around the world, but they are mostly traded from Asia. They are a great flagship for conservation: “You’ve got a fish that’s really cute, the males get pregnant, and they live in some of the most threatened marine habitats

– all the shallow coastal waters and reefs, mangroves, seagrasses – but they also live in the UK.”

Project Seahorse took Heather to the Philippines for the first time, and she formed an intense bond with the place that she now calls her second home. She has helped to launch ZSL projects to protect mangroves: salt-water forests and vegetation that provide habitats for endangered species, as well as protection from the ever-increasing risk of typhoons and extreme weather systems. Working with local teams, she empowers people to set up their own seedling nurseries and re-plant the mangroves. The issue is that mangroves are being cut down to make way for fisheries or other development. It’s a short- term solution – although local people benefit from the fisheries, mangroves are vital for maintaining the ecosystem and protecting communities from storms and extreme weather.

For Heather, her love for the Philippines isn’t just about diving on coral reefs, working on unspoilt sandy beaches and protecting mangroves. “It’s about the people there,” she says. “Our team is amazing. The passion and commitment. As a nation, the Philippines is so happy with so little. It’s a very grounding experience spending time there. It’s also a very family-oriented society. Absolute respect for the elders, absolute joy in encompassing children into everything... and just the sound of laughter.” In the face of ever-increasing natural disasters and destruction of marine habitats, it is often the local ZSL teams who are best placed to guide the disaster aid agencies after a typhoon or an earthquake. Heather frequently finds herself offering advice to charities like ShelterBox and Oxfam, and is always amazed to see how committed local people are to regenerating the conservation programmes after a disaster has swept away homes and livelihoods.

Thousands of miles away from the Philippines is another of Heather’s most adored places. The Chagos islands are uninhabited – although not through choice. The British government evicted the residents in the 1970s to make way for a US military base. There is an ongoing campaign to re-patriate the Chagossians. In the meantime, side-stepping the political minefield, ZSL is focused on this unspoiled archipelago as a marine conservation area, ripe for scientific fact-finding and research into possible ways to resolve the destruction of habitats in other marine areas around the world.

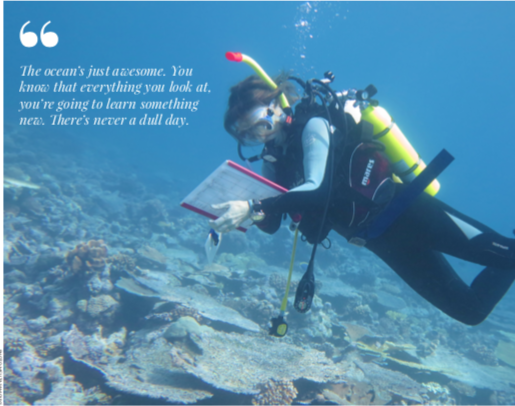

One of Heather’s greatest passions – and the very crux of her job – is problem solving. “It’s very exciting. Looking at new ways of doing things is what’s really fun. And the ocean’s just awesome. You know that everything you look at, you’re going to learn something new. There’s never a dull day. The abundance of fish and the pristine nature of the corals in Chagos is mindblowing. I just get underwater there and squeal like a child.” Fishing is banned around Chagos, and without fishing, it is hard to monitor the sea creatures. Cue a meeting with ZSL terrestrial conservationists who talked about using camera-traps to monitor wildlife on land. Next thing, Heather and her team develop a “GoPro on a fishing line” to act as an underwater camera trap. The issues of the Chagossians have not gone ignored, either: a number of UK Chagossians have been recruited

by ZSL, then trained and employed to work on the scientific studies in their homeland. The hope is that if they someday become re-patriated, they will be true guardians of this pristine marine reservation.

There is seemingly no end to the tendrils of Heather’s work: she’s heavily involved in a ZSL campaign in conjunction with Selfridges. Project Ocean is an unlikely collaboration that saw the luxury department store raising funds, championing messages of marine conservation and setting up a ‘water bar’ and a ‘history of water vessels’ installation to educate people to steer clear of single-use plastic bottles. The food hall has ensured that all of its fish is sustainably sourced, and even convinced Yo Sushi to do the same in every outlet in the UK. Selfridges has used its eye-catching window displays to highlight marine conservation issues, too: with displays such as a panda next to a tuna with the slogan ‘You wouldn’t eat a panda, would you?’ or a shark next to a Champagne cork, with the words ‘You’re more likely to be killed by a Champagne cork than a shark.’

I could go on. Heather and ZSL are at the forefront of so many global campaigns to push governments to commit to protecting their oceans, it’s impossible to list them all. She’s also helped to create an extraordinary connection between a gigantic international carpet manufacturer, Interface (it only uses recycled nylon for its products), and an innovative project to encourage people from ocean-based locales as diverse as Cameroon and the Philippines to collect old and discarded nylon fishing nets and crush them using a non-electric baler (“we invented a baler that’s operated by a car-jack”). They then make money by selling the nylon to Interface. Just thinking about the logistics of extracting the nets and sending them around the world to be incorporated into carpets makes my brain tired, yet this is only one of the strings of Heather’s work.

While she speaks extremely quickly and has an extraordinary recall for the acronyms, statistics and details of every project she works on, Heather is remarkably calm at home in Cornwall. I ask her how she manages to combine work with family life. “I have an amazingly supportive husband,” she says with a smile. “He’s supportive and proud and that’s just priceless. I do feel guilty a lot. My sister-in-law told me: ‘as soon as you decide to be a working mother, you’re going to feel guilty. You have to just get over it.’ But it is really difficult.”

She is incredibly proud of her children: “Both of my kids’ reports stated that they’re very inclusive, tolerant and with a real interest in the world and in diversity. For me, that’s the nicest thing to read in a report, versus academic achievement.” And she firmly believes that living in Cornwall is the best thing they could ever have done. “We chose to live here because I couldn’t imagine us growing up as a family not connected to the ocean and everything that’s important to me.” As soon as she gets back home, she says, she immerses herself in family life: baking with the children, walking with her husband and dog on the beach, stand-up paddle-boarding en famille down the Helford River... Life for Heather is both nomadic and incredibly grounded – with an ever-present connection to the ocean.

net-works.com

selfridges.com/GB/en/content/project-ocean

projectseahorse.org marinereservescoalition.org/2014/06/08/building-ocean-optimism/(check out #oceanoptimism)www.zsl.org/blogs/conservation/when-the-wind-blows