Lilac-tinted Spectacles

‘Heaven knows I’m not miserable now’, to bastardise a Morrissey line.

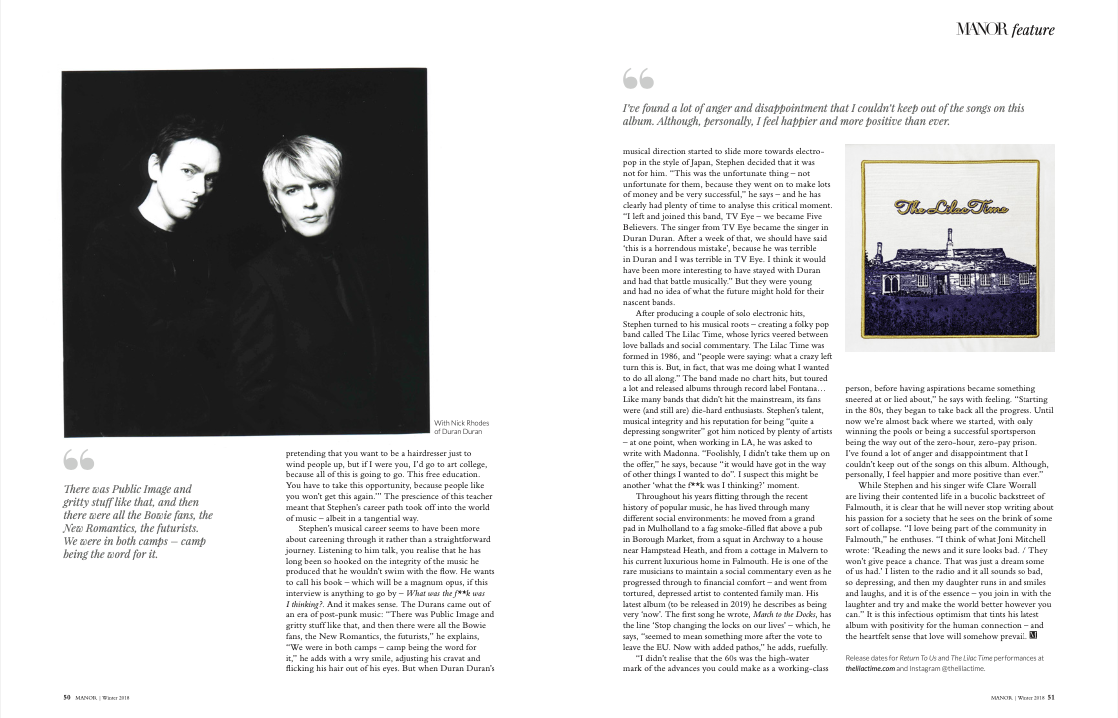

Stephen ‘Tin Tin’ Duffy has been part of so many music scenes in his lifetime, and throughout it all he was known as ‘that bloke who wrote miserable tunes’. Today, he lives in a palatial Georgian house, set back from a tucked-away street in Falmouth with his wife and young daughter. And he couldn’t be happier.

This is a singer-songwriter-producer whose range and realm of work spans four decades. He has made 3,000 songs. He has been a solo artist and performed as part of a band that never quite smashed through the ceiling of big-hit success. He co-wrote an album with Nigel Kennedy when he was at the height of his fame. He co-wrote an album with Robbie Williams in 2004, when Robbie’s star was arguably at its very brightest.

He made a single with Alex James of Blur and Justin Welch of Elastica at the height of Britpop, and worked extensively with indie rock band Barenaked Ladies. And yet, he thinks, he will always be known as ‘Tin Tin who left Duran Duran’.

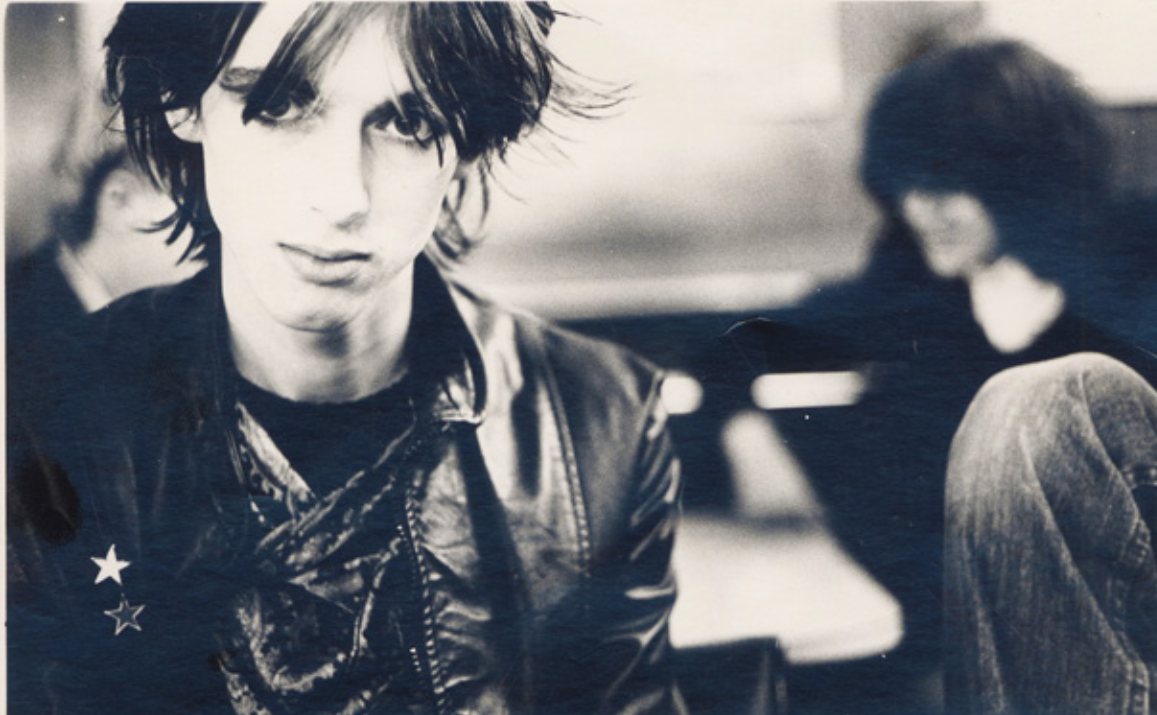

Duran Duran. Formed at the suggestion of Stephen Duffy, just two weeks after he met Nick Rhodes and John Taylor at art college. The band quickly took over their lives (and distracted them from their courses). It was 1979 and life in Birmingham was tough. Most people’s parents, says Stephen, worked on ‘the track’ – the production line at the car factories, or at the Tampax factory.

He grew up in a working-class family in the Washwood Heath suburb of Birmingham. Music was strong in his veins... His granddad was a drummer in big bands in the 30s, 40s and 50s. Two of his cousins followed suit. His mum played The Beatles obsessively. His dad played the flute in the civil service orchestra. “Everyone in my family seemed to play the piano – by ear,” Stephen says diffidently, as though this was quite normal. “Quite jazzy... There was a lot of music,” he muses.

Talking to Stephen at his huge farmhouse table in his cavernous kitchen is like opening the door to an aural museum of music memorabilia – with a good dollop of social history thrown in. But more importantly – it is funny. Stephen peppers his anecdotes with dry asides with the deft art of a seasoned comedian.

He is, above all, a lyricist. While he never thought of himself as a poet, it was the lyrics that drew him in as much as the music. He used to write down Beatles songs and take them into school and learn them in the toilets. This was in the 60s, he remembers: “when they took all the doors off the classrooms. They were experimenting...” he pauses, before adding, “they put all the doors back on, because they realised how noisy it was.”

The times, he says, were very liberal: “I got to secondary school and I didn’t know what a division symbol was. They had showed it to me, but I hadn’t taken it in, because I spent more time reading books and looking through the Encyclopaedia Britannica. And doing crazy xylophone improvisation lessons...” Back then, for kids at Washwood Heath Comprehensive, the choices were limited: careers for boys mostly limited to becoming car makers or bin men – “and if you could read, you became a teacher.”

It was an inspiring form teacher at the end of the 70s who realised that, with the coming of Thatcher, the heady days of 60s liberalism in education were about to close down for good. “He told me, ‘I know you’re pretending that you want to be a hairdresser just to wind people up, but if I were you, I’d go to art college, because all of this is going to go. This free education. You have to take this opportunity, because people like you won’t get this again.’” The prescience of this teacher meant that Stephen’s career path took off into the world of music – albeit in a tangential way.

Stephen’s musical career seems to have been more about careening through it rather than a straightforward journey. Listening to him talk, you realise that he has long been so hooked on the integrity of the music he produced that he wouldn’t swim with the flow. He wants to call his book – which will be a magnum opus, if this interview is anything to go by – What was the f**k was I thinking?. And it makes sense.

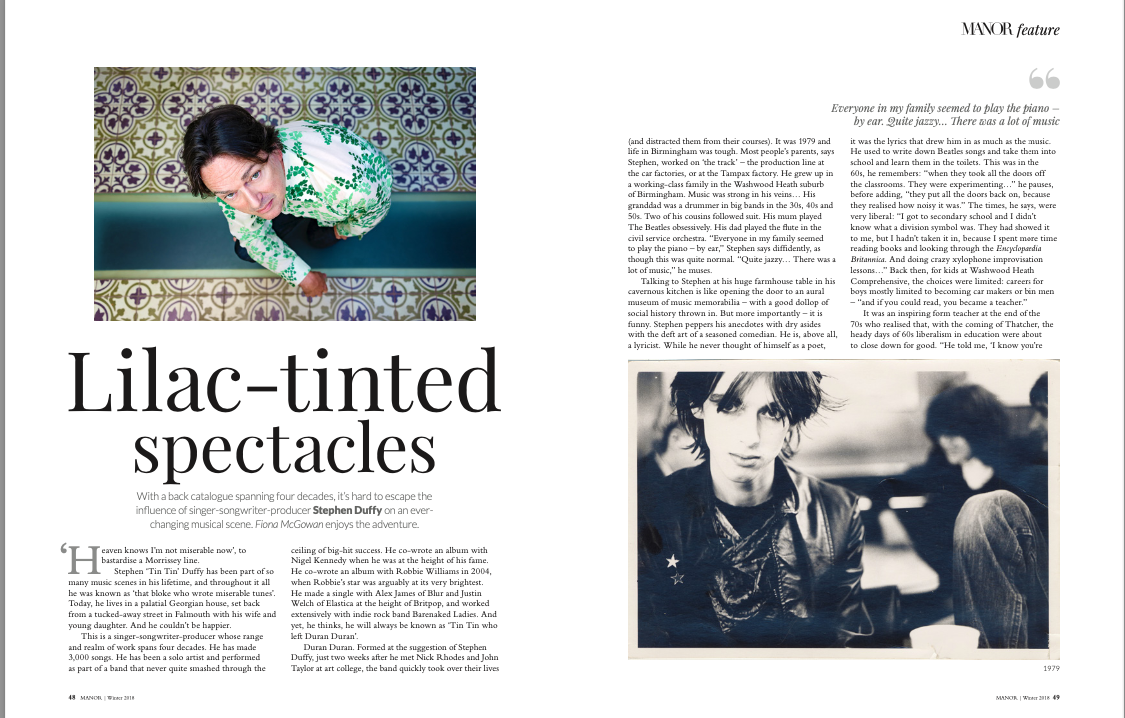

The Durans came out of an era of post-punk music: “There was Public Image and gritty stuff like that, and then there were all the Bowie fans, the New Romantics, the futurists,” he explains, “We were in both camps – camp being the word for it,” he adds with a wry smile, adjusting his cravat and flicking his hair out of his eyes. But when Duran Duran’s musical direction started to slide more towards electro- pop in the style of Japan, Stephen decided that it was not for him. “This was the unfortunate thing – not unfortunate for them, because they went on to make lots of money and be very successful,” he says – and he has clearly had plenty of time to analyse this critical moment.

“I left and joined this band, TV Eye – we became Five Believers. The singer from TV Eye became the singer in Duran Duran. After a week of that, we should have said ‘this is a horrendous mistake’, because he was terrible in Duran and I was terrible in TV Eye. I think it would have been more interesting to have stayed with Duran and had that battle musically.” But they were young and had no idea of what the future might hold for their nascent bands.

After producing a couple of solo electronic hits, Stephen turned to his musical roots – creating a folky pop band called The Lilac Time, whose lyrics veered between love ballads and social commentary. The Lilac Time was formed in 1986, and “people were saying: what a crazy left turn this is. But, in fact, that was me doing what I wanted to do all along.” The band made no chart hits, but toured a lot and released albums through record label Fontana... Like many bands that didn’t hit the mainstream, its fans were (and still are) die-hard enthusiasts. Stephen’s talent, musical integrity and his reputation for being “quite a depressing songwriter” got him noticed by plenty of artists – at one point, when working in LA, he was asked to write with Madonna. “Foolishly, I didn’t take them up on the offer,” he says, because “it would have got in the way of other things I wanted to do”. I suspect this might be another ‘what the f**k was I thinking?’ moment.

Throughout his years flitting through the recent history of popular music, he has lived through many different social environments: he moved from a grand pad in Mulholland to a fag smoke-filled flat above a pub in Borough Market, from a squat in Archway to a house near Hampstead Heath, and from a cottage in Malvern to his current luxurious home in Falmouth. He is one of the rare musicians to maintain a social commentary even as he progressed through to financial comfort – and went from tortured, depressed artist to contented family man. His latest album he describes as being very ‘now’. The first song he wrote, March to the Docks, has the line ‘Stop changing the locks on our lives’ – which, he says, “seemed to mean something more after the vote to leave the EU. Now with added pathos,” he adds, ruefully.

“I didn’t realise that the 60s was the high-water mark of the advances you could make as a working-class person, before having aspirations became something sneered at or lied about,” he says with feeling. “Starting in the 80s, they began to take back all the progress. Until now we’re almost back where we started, with only winning the pools or being a successful sportsperson being the way out of the zero-hour, zero-pay prison. I’ve found a lot of anger and disappointment that I couldn’t keep out of the songs on this album. Although, personally, I feel happier and more positive than ever.”

While Stephen and his singer wife Clare Worrall are living their contented life in a bucolic backstreet of Falmouth, it is clear that he will never stop writing about his passion for a society that he sees on the brink of some sort of collapse. “I love being part of the community in Falmouth,” he enthuses. “I think of what Joni Mitchell wrote: ‘Reading the news and it sure looks bad. / They won’t give peace a chance. That was just a dream some of us had.’ I listen to the radio and it all sounds so bad, so depressing, and then my daughter runs in and smiles and laughs, and it is of the essence – you join in with the laughter and try and make the world better however you can.” It is this infectious optimism that tints his latest album with positivity for the human connection – and the heartfelt sense that love will somehow prevail.

Release dates for Return To Us and The Lilac Time performances at thelilactime.com and Instagram @thelilactime.